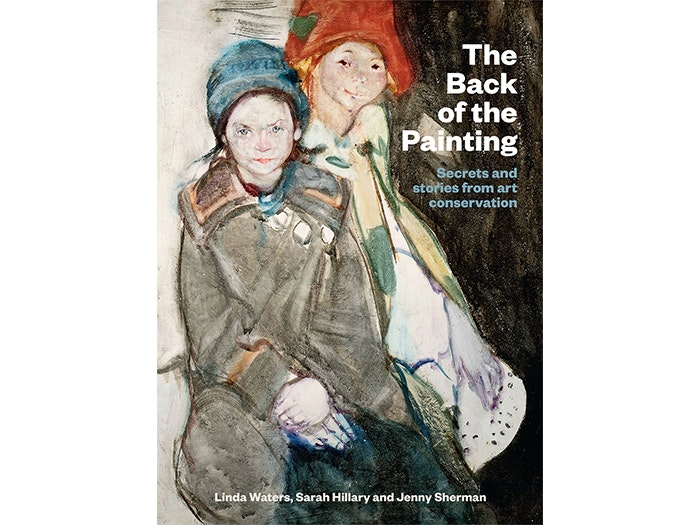

The Back of the Painting

Behind the scenes with the experts on famous paintings

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Linda Waters, Sarah Hillary, and Jenny Sherman discuss The Back of the Painting, with Te Papa Press.

(Left to right) Jenny Sherman, Sarah Hillary and Linda Waters in the conservation lab at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa

Linda Waters is Conservator Paintings at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and has particular interests in the treatment of paintings from the midtwentieth century onwards and how the material nature of artworks contributes to their narrative. She has expertise in the microscopy and analysis of paint crosssections and has undertaken research on artists’ pigments.

Sarah Hillary is Principal Conservator at the Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki and specialises in the study of historical artist’s techniques. She has published research on New Zealand artists Colin McCahon, Rita Angus and Frances Hodgkins, and international artists James Tissot and Guido Reni. She has also been involved in curating exhibitions about artist techniques. Sarah is also a practising artist.

Jenny Sherman is the Conservator at Dunedin Public Art Gallery and specialises in European Old Master paintings with particular emphasis on Italian works. She has carried out treatment and technical study of paintings ranging from the 13th century to the present day. She has worked at the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco and the Conservation Center at New York University. She ran a private conservation practice in New York for many years before moving to New Zealand.

LW: Jenny, Sarah and I first started talking together about the idea in mid-2019. However, I had been thinking about the concept well before then, early in 2018, having provided information along similar lines for a digital interactive for the portrait wall in Toi Art, the new exhibition at Te Papa.

LW: I wanted to share more broadly the really fascinating things we see in the course of our work that the public, and even others in the museum rarely get to see. One sage piece of advice from a colleague was to ‘speak with your own voice,’ so I saw the book as an opportunity to do that – to meld my professional observations with a more personal response to art and my career in conservation.

Jenny Sherman: I was delighted to be invited to join this project – especially so to be working with my colleagues, Linda and Sarah, where we could discuss individual paintings from our respective institutions and share our knowledge with the public about this ‘hidden world’ of what we see on the backs of paintings and how to interpret it.

Sarah Hillary: To have an opportunity to work closely with Linda and Jenny, who I had always admired as conservators. I was also keen to produce a publication that revealed more about the fascinating work that we do and that would show that it is not just about ‘fixing things’, but really looking and understanding the material, as well as the historic and conceptual aspects that make up a work of art. It is a real privilege to get this close to them and to be responsible for their care.

JS: We each selected a substantial group of paintings from our respective galleries that either had something interesting on their backs or had an intriguing story connected to the back.

LW: Having discussed ideas for paintings we would include remotely, we three authors met at Te Papa late in 2019 armed with coloured images of the fronts and backs of all our paintings of interest. And, in what was such an exciting highlight in the process, we laid the images out chronologically on a couple of long tables. At that moment we saw the material diversity and visual potential of the book, which was just wonderful – it was certainly a stimulus to proceed. There’s a photograph of this moment in the lab in the back of the book [p.230] – I love this image! This is also the moment we saw that the paintings we had selected spanned 500 years! At that point, we also did a bit of rearranging and culling to avoid replication and to ensure we had a fairly consistent chronology. We began our writing from there.

My selection was from paintings that I had come across in my day to day work, in the six or so years I have been working at Te Papa – paintings that I knew well and that had interesting stories to tell. There was a plethora of choice, so personal interest played a part, as did aiming to cover a broad range of styles, dates and materials. The genesis of storytelling around the backs was the little painting of Anemones by Flora Scales which I was preparing for loan, so that was going to be my first entry. I also wanted to include a painting that I had seen in storage many times, one that always fascinated me as it had clamps on the back! I had to get to the bottom of that!

SH: We wanted a range of work, but I especially wanted to include the results of detailed research I have carried out over the years so I selected examples that I hope tell a bit of a story about some of those discoveries. I also chose two examples that were very interesting but that I didn’t know a lot about – they proved to be quite a challenge.

LW: We had some initial discussions remotely over a few months to flesh out the idea, plus we met again in person early in 2020 once we had written our first entries, just prior to Covid! After that we more or less worked in parallel, keeping in touch remotely, reviewing and discussing each other’s ideas as we progressed. I wrote the introductory essay, having discussed the content with Sarah and Jenny, and running it past them for review.

JS: After agreeing upon which paintings to include, each of us wrote our own entries. We had an early session after writing two or three entries that we then shared with each other to see if we were all on the same page and if our voices would work well together. Once we were satisfied with that, we just kept on writing and shared entries occasionally. Zoom meetings during lockdown proved essential and always provided a shared sense of camaraderie during that strange time.

SH: When we all met in Wellington in 2019, it was really Linda’s brilliant idea that ‘more’ was better. So we produced a wide range of paintings that spanned the centuries from around the world and wrote about 10 each. We shared our first drafts and discussed how we might write in a way that was from our personal perspective and with our own voice, but hopefully worked as a publication.

I was seriously wondering when I would get time to write as work seemed so busy, but then we went into lockdown. Ironically for a conservator, being separated from the object and working from memory turned out to be the perfect writing environment, giving me time to think. Access to computer information was intermittent but I received a great deal of help from various friends and contacts via email.

The book was Linda’s idea and she has been the one to drive the project, so it seemed really appropriate for her to write the introduction. We discussed the material that would be good to cover, but it was important to have one clear voice in the introduction. Linda has taken a refreshing and personal approach and the result is a wonderful piece of writing.

JS: Oh, without a doubt! There are so few of us that it becomes essential to consult colleagues when needing advice. None of us is an expert in everything and it’s very reassuring to confer with a colleague who may have knowledge of something you don’t.

LW: The profession is very collegial – we often turn to our national and international colleagues for technical advice and help with problem solving because of the complexity of what we do.

SH: In my experience, conservators and members of the NZCCM are all very collaborative and collegial. There are so few of us, we can benefit a great deal from helping one another. I have also found conservators working internationally can be extremely helpful, particularly if you have an investigation that is of interest to them. We all have limited time but will help when we can.

JS: The Ray Thorburn painting is the most remarkable for me. After viewing the face of the painting, it’s so unexpected; I’ve never seen anything like it before.

LW: For me the most remarkable story is that of the portrait of Dr Gray Hassell – once a double-portrait, which we found to have been cut in half by his second wife.

SH: I think it is remarkable that Poedua by John Webber is unlined and almost untouched in its original frame, after more than 200 years.

JS: Among the paintings that I wrote about, I found the story of Esther Levi-Pissarro’s label requesting that her husband’s paintings not be varnished to be quite touching. Closing it off with ‘yours truly’ and signing the label by hand made it so personal, and demonstrated the high regard she had for his legacy.

LW: I think the most poignant is the Tony Fomison work Wildman (1973), because of the way he has used found materials to make a canvas. The materials, particularly when one sees the painting from the back, express so much about his need to paint and the intensity of his creative activity.

SH: My choice is Untitled by Julian Dashper.

JS: Well, I started in my career before the internet was around, and all photography was done on film! Certainly digital technology has grown in leaps and bounds, enabling us to share, access, compare and store all kinds of images and data. As digital equipment has evolved, in many cases much of it has become more portable. This is certainly true for, say, X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) which provides elemental analysis of an artwork. XRF is also among the many non-destructive analytical techniques that have emerged, that no longer require removal of a physical sample from an artwork. On a daily basis I’m even able to achieve so much at work just using my iPhone; I’d be lost without it!

LW: Analytical techniques have become more advanced, such that portable devices can now be used to gather a lot of information.

SH: My career has been quite long so my feeling is that the digital revolution has been the greatest factor. It is much easier to do all sorts of analysis and carry out research than it was previously. So much is online, and we can chat to experts on the other side of the world with relative ease.

JS: Materials, equipment and tools are constantly being developed. For example, we’ve seen great progress in the development of more stable artists materials, new cleaning methods that can be more finely tuned for specific purposes, and portable analytical and imaging capabilities. I think much of this type of progress enables conservators to be much less interventive in their treatments.

LW: As the field has developed, the approach to treatment has become more sophisticated and one can approach aspects of the work more selectively. For example, developments in the chemistry of cleaning and the understanding of modern paints means solutions can be tailored very specifically to the materials one is trying to remove or reduce, in ways that were not possible a decade or two ago.

SH: Absolutely, as our approaches have become much more interdisciplinary, consultative, preventive and holistic in focus. There is also much greater respect for the concepts behind the artwork and an acknowledgement of the importance of different cultural approaches.

JS: Well, it’s a lovely way for readers to gain insight into the way we approach visual evidence to gain an understanding of how an artwork was made, or what has happened to it during its history. The book also provides a window into an aspect of what we conservators are privileged to see on a routine basis, allowing us to share it with a much wider audience.

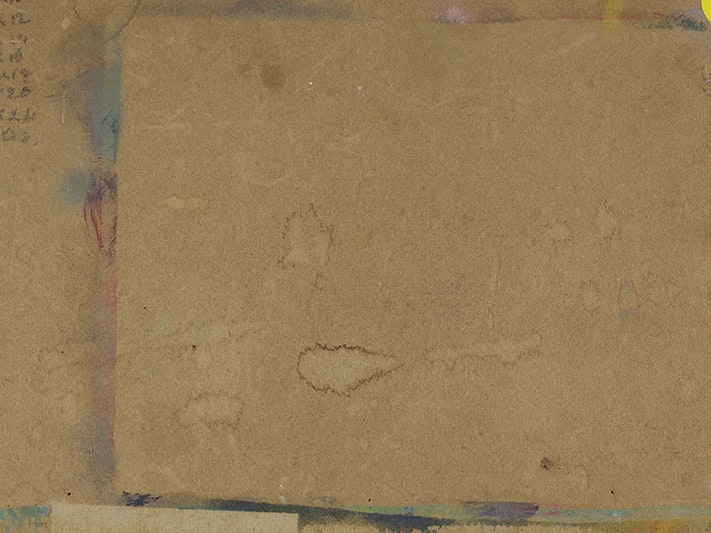

SH: That a painting cannot be fully appreciated as a digital image or page on a book, there is so much more to it. They are three-dimensional objects, with textures, hidden markings and even smells. They contain a wealth of information about the artistic process and their fascinating histories.

LW: I hope readers will see that there is much to look at in the actual materials from which paintings are made, and that looking at them complements art historical and other cultural information when trying to understand artworks. And I hope that they see it can be a good place to start to try to understand paintings! In writing this book I was also able to express a personal response to paintings (from my material observations), and I would like to think that this might facilitate readers to do the same.

Behind the scenes with the experts on famous paintings

Based on the new book ‘The Back of the Painting’ from Te Papa Press, view a work from our collection – both the artwork and what is on the back of the painting – and unpick the story it tells.

Closed

Apr 8 – Jul 29 2021

Exhibition Ngā whakaaturanga

Revised edition of the award-winning biography of one of New Zealand's most famous women artists.