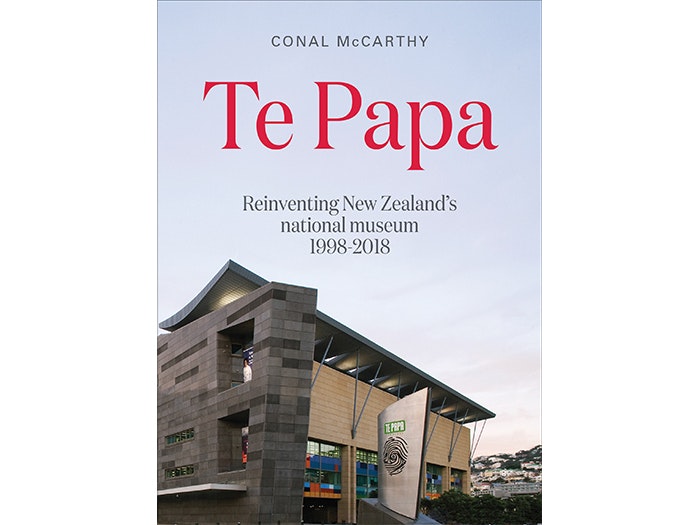

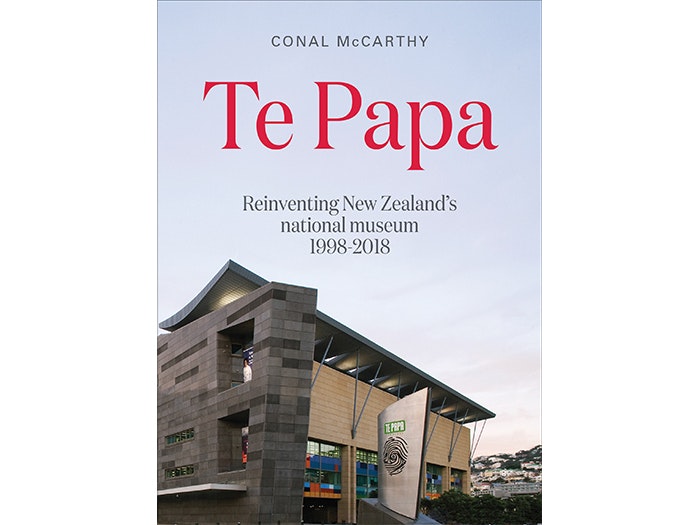

Q&A with Conal McCarthy, author of Te Papa: Reinventing New Zealand’s National Museum

Conal McCarthy discusses Te Papa: Reinventing New Zealand’s National Museum with Te Papa Press.

Conal McCarthy is the programme director of the Museum and Heritage Studies programme at Victoria University of Wellington. He has degrees in English, Art History, Museum Studies and te reo Māori. He has strong links with museums, art galleries and heritage organisations around New Zealand, and has worked in a variety of professional roles including education and public programmes, interpretation, governance, collections and curatorial work. His academic research interests include museum history, theory and practice, exhibition history, Māori visual culture and contemporary heritage issues. Conal has published widely on the historical and contemporary Māori engagement with museums, including Exhibiting Māori: A history of colonial cultures of display (2007), Museums and Māori: Heritage professionals, indigenous collections, current practice (2011) and Museum practice: The contemporary museum at work (2015) in the series International Handbooks of Museum Studies.

"But if you don’t record history as it happens, it disappears, and there is nothing to write about, or learn from." – Conal McCarthy

You are a former staff member at Te Papa, and you were there on the Museum’s opening day 20 years ago. Was working on this book a sentimental journey?

Yes, definitely. I drew on a lot of memories as well as previous historical material I had used in other writing on Te Papa, and reached out to former colleagues from the project office – checking details, finding images, getting input on the text – that was fun for all of us. As Professor Simon Knell says in the preface, I was a product of the time as much as the museum I write about. It is easier to see in hindsight how Te Papa was a product of New Zealand history and culture at that time. It is much harder to see where it is going now, but an in-depth knowledge of institutional memory is always helpful in that regard.

What else was it?

It was writing a history of the present, compiling an historical record of an important, and even momentous, period in late 20th century New Zealand society that is quickly receding into the past, and how it has been reflected in the national museum. The 1980s and 90s produced a remarkable museum that was and is world-leading. However, this history is something that current staff in New Zealand museums (and even at Te Papa itself) often know little about. Museum history is hard to capture because institutions today are often ‘presentist’, and don’t have time to look back at where they have come from. You know the old adage: those who don’t know their history are prone to repeat it…

What exactly was so ground-breaking about the new Museum that opened on February 14 1998?

It was innovative in so many ways: the interdisciplinary mission, the public engagement with broad audiences, the positioning of the museum in a commercially positive/leisure space, the technology (for the time) including computers/interactives/playful exhibits and accessible labels, the interpretation and visitor focused exhibitions, and of course what was called the bicultural/Treaty-based experiment, which is still a model of indigenous empowerment for the rest of the world. International scholars and museum professionals reference Te Papa in their work – from the hosts in bright shirts and integration into a (tourist) experience economy to its Māori name and bicultural leadership structure. Simon Knell says it’s the most influential national museum of the last 40 years. Of course, museological trends have moved on, and some ideas are now 30 years old, but it is nevertheless important to always contextualise and historicise museums in their setting, to consider what they did and why, and to think about the future of the national museum in that light. Taking the long view makes the present look different.

Did what the public encountered on that day fully realise its aspirations to that point?

In some cases, they were well and truly exceeded, like getting two million visitors in its first year. In terms of overall public engagement with exhibitions, Te Papa was spectacularly successful – any museum that attracts over 25 million visitors in 20 years has to be doing something well. Māori and iwi embraced Te Papa and the concept of mana taonga, which contributed to the overall success. However, in some ways, the integration of collections/exhibitions and interdisciplinary representation of New Zealand art, history, nature and culture did not always live up to the promise, and ended up being more cautious than it might have been. The design was also perhaps more conventional than other museums of the period. And of course, some people in the art community have complained ever since the early 1990s that they wanted a separate art gallery – art set apart from the social – but in the wider perspective this has to be seen as a very elitist response to something that is publically funded for the many, not for the few.

Looking back, were any of those hopes and aspirations naïve?

They always are, but that is no reason not to dream, to aspire to change, to try and improve peoples’ lives. Perhaps the thing that has changed most is the cultural nationalism of the 1980s and after, which has largely matured and been left behind (except by politicians). Biculturalism has arguably reached its use by date and is being superseded by more independent and autonomous models of Māori development post-Treaty settlement. The promise of the digital has also faded – the utopia of new technology – as we move into a post-digital age, where there is a return to the ‘real’, the material, and the local. In some cases I sense a return to basics, to core functions, to what museums have always done well. The ‘new’ museology is now quite old. New paradigms and concepts will come along and reshape museums in order to respond to new concerns: climate change, migration and super diversity, youth suicide, Māori cultural futures.

How has the Museum evolved in the past 20 years?

In the last chapter and appendix I talk about this, and try to list just a few of the many events, projects and initiatives at Te Papa since the 1990s – everything from virtual visitors, to travelling exhibitions, to the Matariki festival – but the focus is really on day one and after. This is a history, not a crystal ball, and you certainly can’t capture everything (or everyone). Times have changed, but some of the core concepts and approaches are still there, while others have evolved over time. Collecting, of course, is ongoing but this has evolved as well. Policy and practice are in a constant state of flux.

Is it now a different place to what the project team strove for in 1998?

Yes and no. There are still a few staff who were there at day one. Some of the methods and principles have remained, others have completely changed. Like any museum, there is a burst of energy in a project, then a switch to operational mode. What I have tried to do with this book is provide a record, and show how the exhibitions, programmes and policy grew out of the time and place – which is what those who work at Te Papa now engaged in ‘renewal’ are doing for their own times. History is made, so it can be unmade and remade.

What struck you about coming back into the Museum to do your research for this book?

I still know my way around, and recognise a few familiar faces, but 1998 is now 20 years ago – where did the time go?! Also, I learnt that it is quite a challenge to write a history of which you are a part.

What’s one new thing you learnt while working on it?

I was really surprised to learn that the history of this prominent national museum was not well documented. There is an extensive academic literature, but much of it is not grounded in practice, and lacks an internal understanding. We need histories of museums that balance theory with history and practice – in other words, contemporary museum practice relies on museum history (and theory) to keep it relevant, robust and ethical. But if you don’t record history as it happens, it disappears, and there is nothing to write about, or learn from. Museums need to interview staff, maintain archives, collect photographs, preserve records, and make their past accessible to researchers and the public.

Now the book is published and you have a bit more time, what are you working on?

A comparative study of indigenous museology in Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand. There are fascinating parallels and differences across the Tasman in contemporary museums and galleries, visible in the ways in which Māori and Aboriginal people engage with mainstream heritage organisations, and do their own thing in their communities. I am also working on a book about Māori engagement with museums and ethnology in the period 1890–1940 for Nebraska University Press. This is a unique episode in the history of anthropology which is attracting great international interest. My next book for Te Papa Press will be a multi-authored volume on the Dominion Museum ethnographic expeditions of 1919–23, which is part of a Marsden-funded project led by Distinguished Professor Anne Salmond at the University of Auckland.

You might also like

Te Papa: Reinventing New Zealand's National Museum 1998–2018

Inside the iconic New Zealand museum that has benchmarked international best practice.