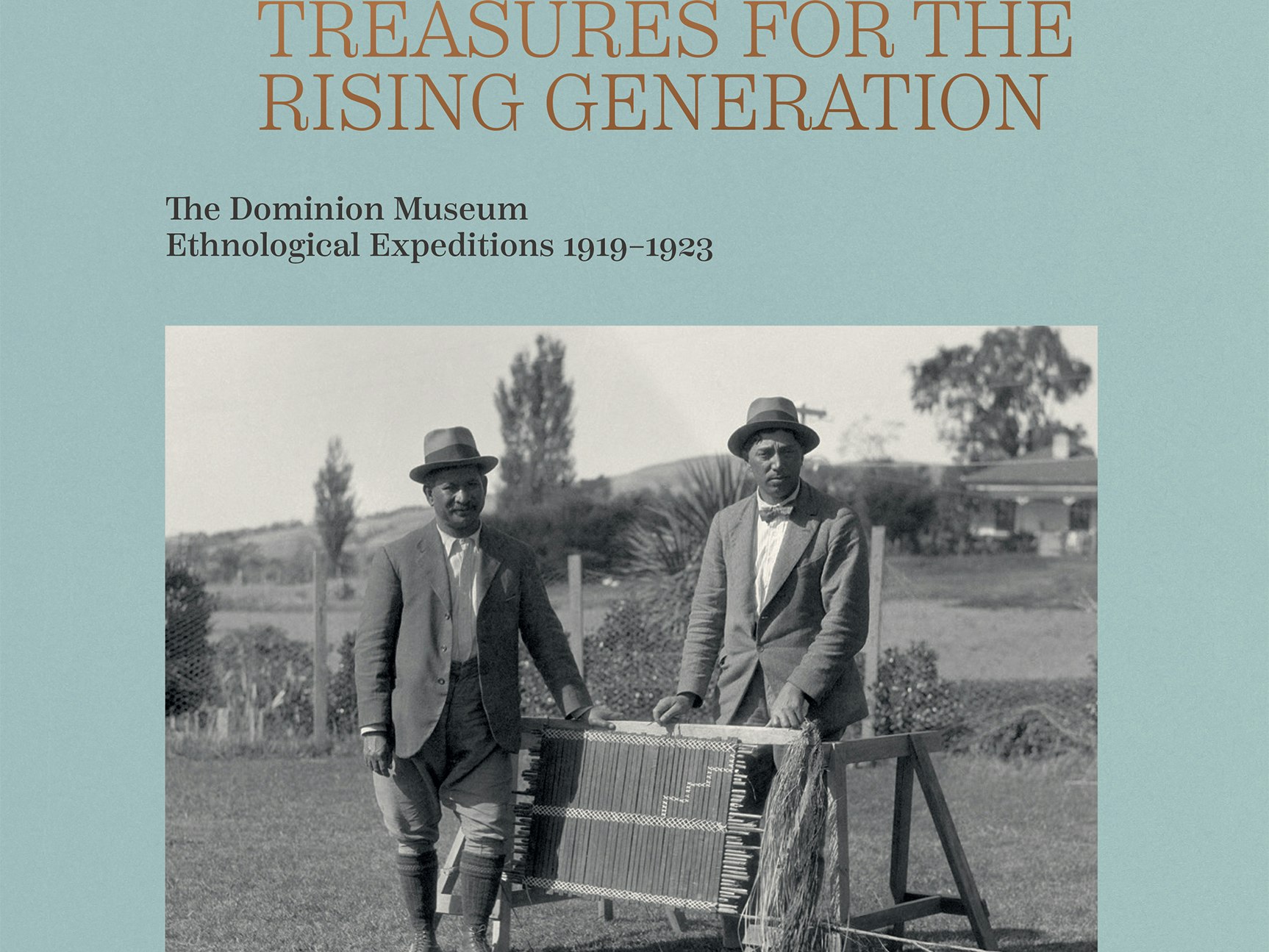

Hei Taonga mā ngā Uri Whakatipu | Treasures for the Rising Generation: The Dominion Museum Ethnological Expeditions 1919–1923

A landmark book about four remarkable museum expeditions that contributed to a recovery of Māori society

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

The authors of discuss the book with Te Papa Press

Wayne Ngata MNZM (Ngāti Ira, Ngāti Porou, Te Aitanga a Hauiti) is a board member of the Tertiary Education Commission, and board chair of Te Taumata Aronui. He is active in the revitalisation of te reo Māori, a specialist in Māori literature, a longtime advocate for Māori art, and an active supporter of the waka hourua renaissance.

Arapata Hakiwai (Ngāti Kahungunu, Rongowhakaata, Ngāti Porou, Ngāi Tahu) is the Kaihautū | Māori Co-Leader at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa and shares the strategic leadership of the National Museum with the Tumu Whakarae | Chief Executive. He has extensive knowledge, relationships and experience working with iwi and museums, including helping to restore the Ruatepupuke wharenui in the Field Museum, Chicago, undertaking a research project to identify and create an international digital database of Māori and Moriori taonga, and more recently helping to return the Motunui Pātaka panels from Geneva to Taranaki. He has long advocated for the decolonisation of museums and was the Culture Commissioner for the New Zealand National Commission for UNESCO from 2015–20.

Dame Anne Salmond ONZ DBE FRSNZ FBA is James McDonald’s great-grand-daughter and a Distinguished Professor of Māori Studies and Anthropology at the University of Auckland, and a leading social scientist. She is the winner of the Rutherford Medal, New Zealand’s top scientific prize, and many international fellowships and awards. She is the author of a series of prizewinning books about Māori life, European voyaging and cross-cultural encounters in the Pacific, most recently Tears of Rangi (Auckland University Press, 2017). In 2021 she was granted the Order of New Zealand, the country’s top award.

Conal McCarthy is the director of the Museum and Heritage Studies programme at Victoria University of Wellington. He has published widely on the historical and contemporary Māori engagement with museums, including the books Exhibiting Māori: A history of colonial cultures of display (Routledge, 2007), Museums and Māori: Heritage professionals, indigenous collections, current practice (Te Papa Press, 2011) and, as co-editor, Colonial Gothic to Maori Renaissance: Essays in Memory of Jonathan Mane-Wheoki (Victoria University Press, 2017) and Curatopia: Museums and the future of curating (Manchester University Press, 2019).

Amiria Salmond is James McDonald’s great-great-grand-daughter and is an independent scholar and historian, who was earlier a lecturer in social anthropology and Senior Curator at the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. She is writing a book on the history of the island of Ulbha (Ulva) in the Scottish Hebrides, which was cleared of the great bulk of its inhabitants in the mid-nineteenth century. Her publications include Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange (Cambridge University Press, 2005) and she co-edited Thinking Through Things: Theorising Artefacts Ethnographically (Routledge, 2007).

Monty Soutar ONZM (Ngāti Porou, Ngāti Awa, Ngāi Tai ki Tamaki, Ngāti Kahungunu) is an award-winning historian. He has published two major research and publication projects; Nga Tama Toa: Price of Citizenship: C Company 28 (Maori) Battalion 1939-1945 (Bateman, 2008) and Whiti! Whiti! Whiti! E! Māori in the First World War (Bateman, 2019). He has also made a significant contribution as a member of the Waitangi Tribunal and in the development of the Te Tai Whakaea: Treaty Settlement Stories Project at the Ministry for Culture and Heritage. He was awarded the Creative New Zealand Michael King Writer’s Fellowship in 2021.

James Schuster (Te Arawa) is a Māori Built Heritage Adviser (Traditional Arts) to Heritage New Zealand Pouhere Taonga. Born and raised in Rotorua into a family that has maintained and practised Māori arts and crafts for generations, his traditional knowledge and skills have been passed down through his family. His great-great-grandfather was Tene Waitere, the renowned Ngāti Tarawhai carver.

Billie Lythberg is a Senior Lecturer in the Faculty of Business and Economics at The University of Auckland, working at the junction of business studies, anthropology and history, with a strong focus on Aotearoa and the Pacific. She co-edited Artefacts of Encounter: Cook’s Voyages, Colonial Collecting and Museum Histories (University of Otago Press, 2016) and Collecting in the South Sea: the Voyage of Bruni d’Entrecasteaux 1791–1794 (Sidestone Press, 2018), and co-created the Artefact documentary series exploring taonga Māori in collections worldwide (Māori Television, 2018 and 2020).

John Niko Maihi MNZM (Ngati Pamoana Atihaunui a Paparangi) is the son of Aperaniko Maihi (Paeroke) and Te Kahui Gray. He actively supports his iwi and his community in his capacity as kaumātua and Pou Haahi Ringatū. A former member of the Whanganui River Māori Trust Board (1988–2017), he has held significant leadership roles in the settlement of the Whanganui River Claims. John is the current chair of Te Puna Mātauranga o Whanganui Iwi Education Authority, convenes Te Pae Matua Roopu and Te Rūnanga o te Awa Tupua o Whanganui, and kaiwhakahaere of Te Rūnanga o Tūpoho and kaumātua for the Whanganui District Health Board and the Whanganui Regional Museum. He is also the kāumatua for University College of Learning Whanganui and was made an Honorary Fellow in 2010. John is Kaumātua and Cultural Advisor to the Whanganui District Council and has taken a leadership role in the development of Te Pataka o Taiaroa since its inception. In 2011, he was made a Member of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to Māori.

Sandra Kahu Nepia (Ngāti Pamoana — Atihaunui-a-paparangi, Ngāti Hinemihi — Tuwharetoa) is marae representative for Koriniti Marae on Te Rūnunga o Tūpoho; Board member of Ngā Tangata Tiaki o Whanganui — Advisory and Audit and Risk; Pou Herenga/Heritage and Community Services Manager at the Whanganui District Library and work in iwi developments within the Whanganui District Council; and Kaikirimana for the tohu Puna Maumahara with Te Wānanga o Raukawa.

Te Wheturere Poope Gray (Ngati Kurawhatia ki Pipiriki), also known as Bobby Gray, is the grandson of Te Wheturere Robert Gray and Ngāraiti Tuatini, and son of Te Wheturere James Gray and Janet McFall. During his working years, from 1951 to the 2000s, Te Wheturere was a primary school teacher and headmaster at primary schools around the North Island. During his years in Tokoroa, Te Wheturere was part of the founding kaimahi responsible for building Papa o te Aroha Marae, and was also a respected kaumātua there once the marae was built. Now retired, he lives at his ancestral kainga, Raetiwha Rāhui in Pipiriki, where he is a respected kaumatua of Paraweka Marae.

Te Aroha McDonnell (Ngāti Hau, Ngāti Kurawhatia, Ngāti Haua, Te Atihaunui-a-Paparangi, Ngāti Maru, Ngāti Maniapoto, Ngāti Tuwharetoa) is a representative of Ngāti Hau to Te Rūnanga o Tamaupoko and Te Rūnanga o Te Awa Tupua.

Natalie Robertson (Ngāti Porou, Clann Dhònnchaidh) is a photographic and moving image artist and Senior Lecturer at Auckland University of Technology, Tāmaki Makaurau. Much of her practice is based in Tairāwhiti, her East Coast Ngāti Porou homelands, where her focus is on her ancestral Waiapu River and the protracted catastrophic impacts of colonisation, deforestation and agriculture. She has exhibited extensively in public institutions throughout New Zealand and internationally. She photographed for the award-winning book A Whakapapa of Tradition: One Hundred Years of Ngāti Porou Carving, 1830–1930, written by Ngarino Ellis (Auckland University Press, 2016).

‘Cultural revitalisation’ is closer to what Apirana was aiming at – i.e. restoring tikanga Māori and ngā tāngata Māori to a state of ora by recording tikanga and te reo for future generations.

Perhaps it’s best understood as using new technologies as memory storehouses – like the wānanga tradition, where whakapapa, kōrero, tauparapara, karakia and so on were memorised and handed down as gifts from ancestors to future generations. Apirana Ngata used a mix of old and new tikanga for this purpose – whare whakairo, kapa haka and mōteatea but also film and sound recordings.

Utterly. He was the visionary and ‘navigator of networks’ that made them possible.

Very significant. Apirana and Te Rangihīroa were also using international ethnology, Best, the Museum and those networks to record ancestral tikanga, while regarding them as imperfect and partial.

Although we have not been able to determine the makes and models of the cameras, we know that James McDonald used both still and cinematic cameras. His main field cameras were quarter- and half-plate folding cameras that used sheet film rather than the glass plates that were used in a studio. The movie cinematic camera used nitrate cellulose 16mm film, which could be quite combustible.

McDonald’s cameras were invited manuhiri – welcomed guests, performing a key role in recording people practising tikanga handed down for generations, such as fishing techniques, weaving, taruke koura or crayfish-pot making and creative arts such as tukutuku. McDonald had an eye for composition, as well as being a superb technician – there was no such thing as shooting on automatic in those times. His photographs are taonga that are a vehicle for mātauranga or knowledge specific to places and people.

Community film screenings prompt many comments on the various practices, infused with great warmth and humour. Looking at the films and photographs about one hundred years later has been described as a collapse in time and space – a space between mauri moe and mauri oho – bringing the long passed subjects back to life.

The Māori creative arts have benefitted from the documentation, particularly the photographs and films, but also through the notebooks left by Te Rangihīroa, through being able to look at the taonga from those times. However, as the documentation has not been widely accessible before now, we anticipate that the rising generations ahead – ngā uri whakatipu - will continue to learn from the extraordinary legacy handed down.

Yes. It was a pleasure to work as a team, and with experts in history and tikanga, archivists, museum specialists and descendants – trying to piece together what happened during the Expeditions, and to understand the tensions, creative strategies and ambitions that drove these earlier collaborative enterprises.

One of our hopes is for what people may bring to the taonga within the book: the restoration of names of people and places, memories, and further taonga passed down through generations – taonga tuku iho. We hope the publication of the book continues the work set in motion by Apirana.

A landmark book about four remarkable museum expeditions that contributed to a recovery of Māori society

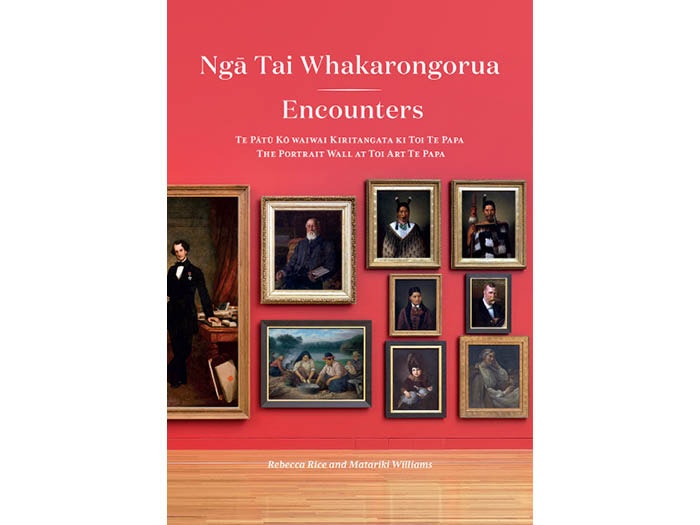

Accessible, informative guide to one of Te Papa’s most popular permanent art exhibitions