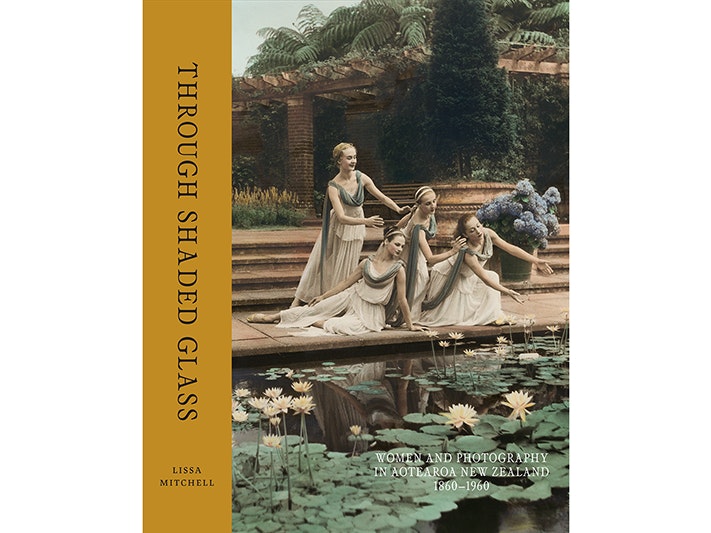

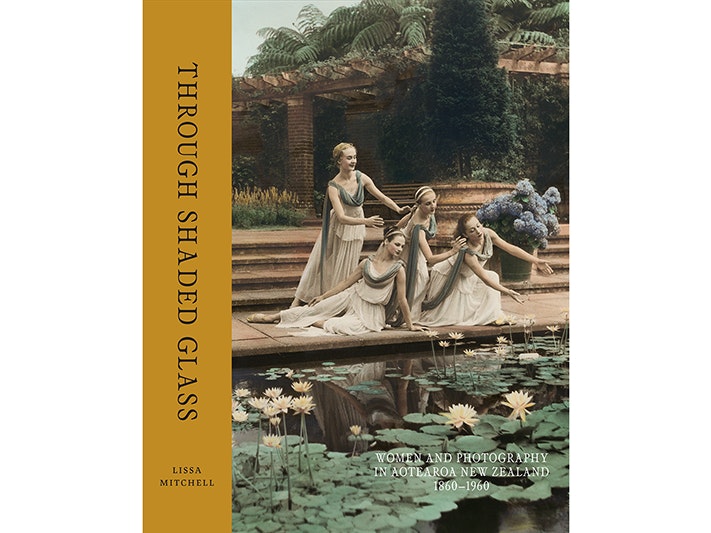

Through Shaded Glass: Women and photography in Aotearoa New Zealand 1860–1960

Shining the light on New Zealand’s women photographers.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Lissa Mitchell discusses Through Shaded Glass: Women and photography in Aotearoa New Zealand 1860–1960 with Te Papa Press.

Lissa Mitchell is Curator of Historical Photography at Te Papa and has held previous roles in photographic collection management and preventive photographic conservation roles at the New Zealand Film Archive (now part of Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision) and the National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa. She has a degree in art history from Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington. Prior to a career in photographic history, Lissa was an experimental filmmaker.

Lissa Mitchell. Photo by Yoan Jolly

It evolved from many years of researching photographs made by Pākehā men during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. I became curious about who else had also used photography during this time and what they did with it. Basic questions really: was there really only a handful of women involved in photography? And why are their legacies largely overlooked?

Also, I wanted to know about Māori who took photographs and disrupt the notion that Māori only appeared in photographs. It also seemed that finding out what was exceptional about our photographic history here in Aotearoa compared with everyone else was to understand more about the women who made photographs here – what aided and limited them. What kind of society made these photographers?

Delving into the lives of the women I was able to locate provided some of that information. The book expands beyond the bias towards the person holding the camera as auteur/artist/maker to discover and include those who contributed to the production of a maker’s output – whether as an individual who collaborated or an employer who ran a commercial studio.

Initially, I rounded up about 20 names to start looking into. Most of these were women who are recorded as photographers here in some capacity but don’t feature strongly in the written accounts of photography here – Elizabeth Pulman, ‘Mrs Hamilton’, Louisa Herrmann, Amy Harper. I thought I would locate more information about them and their working lives and that a publication would showcase them as a specific group of exceptional women in photography here.

However, as research continued the list of names kept growing to well over 400 – and is still growing – and defeated the somewhat ambitious idea I had at the start for the book to be as inclusive as possible. However, the work of giving back from this research will continue beyond the publication of the book and I am seeking to update and share the details of the makers I have found.

I trained as an art historian (but I now see myself as a photography historian) and was therefore taught to focus on the exceptional and on assessing an artist’s significance based on a large body of work. But I didn’t see that approach working to support finding anything much out about the contribution of women to photography here prior to 1960.

A long time has passed now, especially since the 1860s and 1870s, and much information is now lost especially about working-class people. It is very challenging to locate information about women as they were not part of many official records at this time. Often unless something exceptional or tragic happened to them it can be hard to find out more about them.

Also, the majority of photographs were not made as artworks so assessing them as such is unrealistic. The collecting of photography by public institutions and the writing about it has also been selective around similar biases. For example, the archive of a photographer, or studio, is often regarded important simply because it is large and smaller holdings dismissed.

It is also important to acknowledge when cultural artefacts are the work of multiple makers (though only one person’s name or brand appears on it) that manual labour was used to produce the photograph even if we don’t know who those makers were.

It is impossible to know the many different reasons that attracted women to the work of photography and there appears to be no anecdotal accounts (such as diaries) from women employed in photographic studios in the nineteenth century.

However, I think it is possible to see from the women in the book that while many of them started their working lives as domestic labour in private homes, factory work (among which a photographic studio was classed) offered a more desirable alternative. They could be more independent, they walked away from the job at the end of the day, it would have been more social, and there was more chance to progress if they could.

There are so many! During the research phase, I worked on so many people’s family histories to piece together basic life information and finding relevant information was so exciting. I often started with a maker’s name recorded on the mount of a studio portrait and went from there.

A good example was Agnes Williamson. Early on contemporary photographer Caroline McQuarrie, sent me a photo of a studio portrait photograph she saw at Blacks Point Museum in Reefton while she was doing her own research. On the mount under the portrait was printed the photographer’s name: ‘Miss Williamson, Reefton’. It took a long time to confirm who Miss Williamson was – a commercial photographer in Reefton from 1896 to 1907 who had extremely bad luck in becoming responsible for the debts of her brother-in-law.

She attempted to move to Wellington, where she might have restarted her career, but was arrested under the suspicion of trying to leave the country and escorted back to Reefton. While this sad turn of events ended her career as a professional photographer it enabled me to finally locate her. The information about her and her business revealed in the court case allowed me to start the belated work on recording her legacy and tying it to what is left of her work.

When I came across the album of snapshot photographs taken at Ōtāne children’s home by the matron Edith Waller I was very moved. It is a compelling amateur work of photography and album making that records the children living at the home about 1920 and aspects of their lives.

It would have been easy to dismiss it as a simple social history artefact, but it is far more than that. I became interested in finding out more about the home and how it operated and about Waller and the children (though it was not possible to really trace them from their first names).

This became an emotional object for me and it reinforced the power of photography to record a moment or fragment in time and hold it up as something bigger. My mother spent time in children’s homes and orphanages so it hit me in the heart more perhaps because of that.

There are so many and picking out just one feels unfair. But if pushed I would say the portrait of Eila Bristow taken by her studio partner Elsa Mawley (the pair worked as the studio name Bristow Mawley in London and Wellington).

It is stylish, cool and so self-contained – a portrait of a confident photographer taken by another photographer who was also a close friend. I think it conveys much about who Eila and Elsa felt they were and what they were trying to do in their photographic work. I am struck by their ambition and independence and the lead they sought out and took from mentors such as the acclaimed London photographer, Dorothy Wilding.

Well, now I will mention several! The small carte-de-visite portrait of Kate Alderson with the miniature and meticulously hand-painted floral arrangement and headdress made about 1873 by the Clarke Brothers studio in Auckland and an unknown colourist – who was she?

The sublime and sensuous pair of portraits by Auckland studio Bettina (Lily Byttiner) of the Australian dancers Jean Raymond and Elaine Kramer; the candid portrait of German Jewish refugee photographer Irene Koppel in the Spencer Digby Studios, smiling, despite everything she endured as a photographer in wartime New Zealand; and the 1931 portrait of New Zealand actor Isabel Wilford taken in London by Bristow Mawley – sheer modern glamour.

I am looking forward to the book sharing so many of the photographs, and having them seen and responded too – as after all that is what is needed and what will reactivate them as cultural objects.

That there is a particularly forgotten era in writing and collecting photographic history here – the period roughly from the 1890s to the 1920s. This is a complex period of time when there was a vast amount of change not only in photography but also generally.

A time when women come into their own through their use and consumption of photography but also in terms of modern life – working, travelling, conflict.

In photography, there were multiple changes to all aspects of the production and presentation of photographs that people had to adjust to. It was also a time – especially in Aotearoa – that photography became more accessible with the development of Eastman Kodak products for ‘everybody’.

I have learnt so much more about photography through studying this time period and the types, styles and formats of cameras, prints and negatives and other equipment that arrived on the market. It really impacted on me that this was a distinct period of photographic history that was very different to the period from the 1860s to the end of the 1880s.

I came to appreciate the personal archives of other women held in public institutions. Una Garlick’s archive at Auckland Museum, for example, contains her work but also photographic prints by others, which she presumably acquired through a reciprocal trade with other photographers.

Garlick’s archive holds the only surviving photograph I have been able to locate by Beatrice Gibson (or ‘B. A. Gibson’ as she was known as a photographer). This print, a rainy-night scene outside the Dunedin Railway Station, is special as it was Gibson’s most successful photograph and earned her high praise nationally and internationally. We are so lucky that Garlick retained it as it is one of many different versions of the same image Gibson made hence the enduring reception to its continued exhibition.

Other women’s archives that yielded some stunning examples were not photographers but rather successful women in other fields who turned to women photographers to take their portraits. This was the case with the actor Isabel Wilford, who was photographed in London by the Wellington studio Bristow. And Mary Annette Hay, who worked as a promoter for the New Zealand Wool Board and whose archive includes photographs taken by the Wellington studio of Anderson and Atkinson (a partnership between Frances Anderson and Elizabeth Atkinson) of her modelling wool garments. Prints from both these archives feature in the book and really add to the visual richness of their work.

Despite the ease of searching digitalised sources of historical print publications, there are gems to be found by browsing them, too. That is how I came across the portrait taken in Sydney of Mākereti with her Kodak Autographic folding camera.

In this case, the system at the National Library of Australia had misspelt her name – ‘Maggie Papabura’ – so not only was this an exciting and remarkable research find for me but also was able to contact them and get her name corrected. Now if people search they will find her in the pages of the Australasian Photo Review magazine. That’s so satisfying for a researcher.

That for over 160 years women in Aotearoa have had access to photographic equipment and used it in all sorts of ways.

Shining the light on New Zealand’s women photographers.