Dougal Austin (Kāti Māmoe, Kāi Tahu, Waitaha) is Senior Curator Matauranga Maori at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. He has a particular research interest in the origins, development, cultural use and significance of hei tiki. His current work has included a tour of the Kura Pounamu exhibition in China.

"Like many people, I have always loved hei tiki and I have been very fortunate over the years to work with many of these beautiful adornments held in the taonga Māori collections of Te Papa and elsewhere." – Dougal Austin

More than 50 years has gone by since the last book came out devoted solely to hei tiki: the booklet Hei-Tiki by H.D. Skinner of the Otago Museum, published in 1966. Why that long absence, do you think?

Well, there has been some writing about hei tiki since, in articles and chapters of books, but not a substantial stand-alone book. It’s about time isn’t it? It has been quite a challenge to bring a fresh perspective to looking at hei tiki and say something new and interesting. I think that has been part of the reason why it has taken so long.

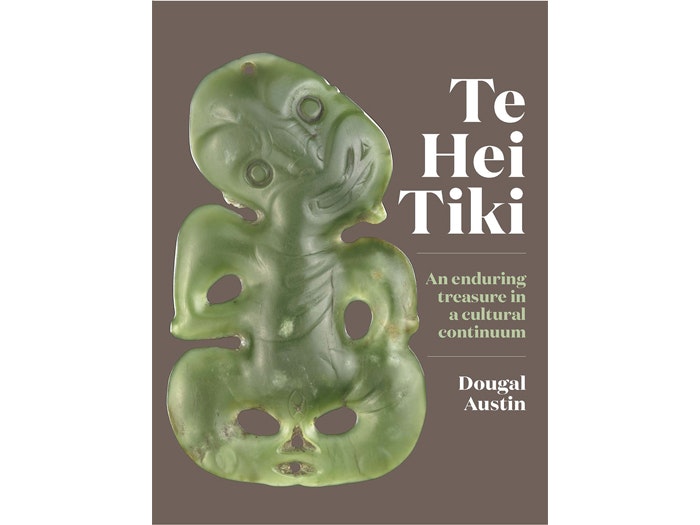

Te Hei Tiki: An Enduring Treasure in a Cultural Continuum developed out of your Master’s thesis at Victoria. What first drew you to hei tiki as the focus of your academic research?

I had a strong feeling it would be worthwhile – that many of the ideas about hei tiki needed to be looked at anew. And I figured that if I was going to put so much time and effort into researching something, it had better be something I was passionately interested in. I had already developed a strong interest in pounamu when curating the Kura Pounamu exhibition. In a sense, researching hei tiki has been a natural progression from that. Like many people, I have always loved hei tiki and I have been very fortunate over the years to work with many of these beautiful adornments held in the taonga Māori collections of Te Papa and elsewhere.

How challenging was it to establish their true story and real essence?

Hei tiki are quite enigmatic taonga, so yes, very challenging. They have many uses and meanings that might change depending on circumstance of the moment or throughout historical time periods. I don’t know if anyone will ever be able to know whether or not they have really established their ‘true story’ and essence. But by grounding hei tiki within the long continuum of Māori culture, which stretches from ancient origins to the current day, I think I’ve had a good go at it.

Is there one particular hei tiki in the book you are especially interested in, or drawn to?

I have a personal connection to a large hei tiki shown in the book, which was found in Otago and subsequently named Hine-matakura. In 2001 I intercepted this hei tiki on its way to auction in Wellington. As a recently found taonga tūturu, it was not something that could be legally sold on the market. I was pleased to see it placed into the custody of tangata whenua from the north Otago area and to know that I played a part in bringing that about by being in the right place at the right time. I guess I’ll always feel a strong sense of connection with this hei tiki.

Is there a wairua surrounding each of them?

One of the artists profiled in the book talks about the Māori wairua that extends across all of the Māori art forms. It’s certainly present in hei tiki. The artists imbued wairua or spiritual essence into the hei tiki they worked, and this has been added to by generations of wearers, who while wearing, handling and rubbing the features smooth have added some of their own wairua to the taonga.

Your book makes some real breakthroughs in explaining the existence of regional styles. How difficult was it to establish their existence?

It was very difficult. Hei tiki are small, durable and portable taonga, which were coveted by many. They could travel large distances over time, throughout generations, by various means such as gift, exchange or spoils of war. So it is difficult to be sure of the origins of most old hei tiki, as the whakapapa of ownership is usually not known now. Even so, I have made some general observations about regional styles, some of which are new.

It also busts a few early misapprehensions and myths, doesn’t it?

There is a long history of theorising and speculating about hei tiki by various authorities. In writing the book I have had to chart my own course through all of that. One of the things I investigated was the idea that a great many hei tiki in collections are trade items made to satisfy European demand. By studying the extent of surface wear – indicative of extended use by Māori – I came to the conclusion that most hei tiki had received significant use by Māori before they ended up in collections. European collector ‘trade-tiki’ exist but they seem to be fairly rare. There are a number of other points of difference between what I have to say and the longstanding views of others.

Visiting contemporary carvers and talking with them about their work is a very rich part of this book. How are they part of the cultural continuum in which hei tiki sit?

It was a pleasure to work with contemporary makers of hei tiki in the writing of this book. I enjoyed seeing their passion and the high level of cultural integrity they bring to their practice. They are part of a long tradition of hei tiki making and part of a long tradition of innovation and experimentation (making use of contemporary tools, materials and techniques of the day). They understand the cultural responsibility that comes with their practice, upholding high standards and ensuring that the hei tiki art form continues to grow and flourish, that it is passed on into the future in good shape. They are at the leading edge of the cultural continuum fashioning contemporary hei tiki, which in time will be looked back on in appreciation as quality expressions of Māori culture dating to the current era.

What’s one new thing you learnt while working on this book?

There are so many new things I’ve learnt, but one special highlight was sitting out under a tree watching stone working revivalist Phil Belcher carve hei tiki using old techniques. This was a profound learning experience. I had never seen that before. I was really interested in how Phil drilled out the eye grooves using a length of hollow bird wing bone attached to a tūwiri ‘cord drill’. And it was a good thing photographer Norm Heke was on hand to capture that for the book.

Te Papa has the biggest collection of hei tiki in the world. Is it constantly being added to as more hei tiki are put into the care of the museum, or purchased when they come up for sale?

I think the hei tiki collection at Te Papa probably is the largest in the world, and we are continuing to add to it through acquisitions, whether that be via purchase or as generous gifts, which also happens. No two hei tiki look exactly alike. To my mind, the variety adds greatly to the appeal of building up the collection, enabling a large number of hei tiki to be shown in exhibitions or in books such as this. We are also acquiring more contemporary hei tiki reflecting the continuity and continuing innovation of the art form.