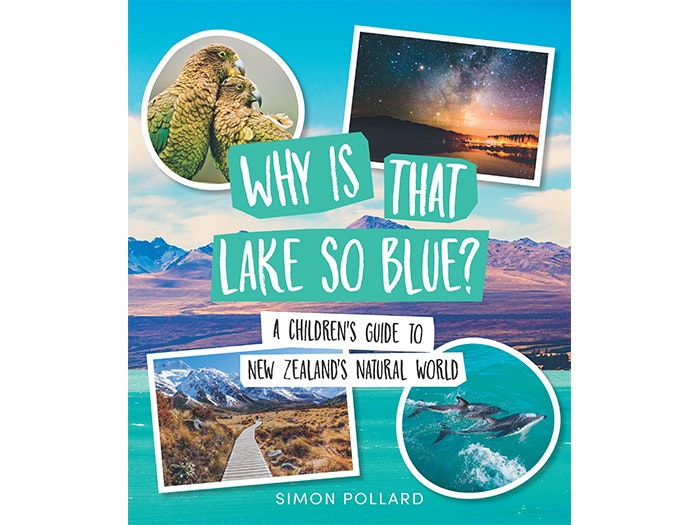

Why is That Lake So Blue?

A fascinating, fun and engaging book on New Zealand’s amazing natural world

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

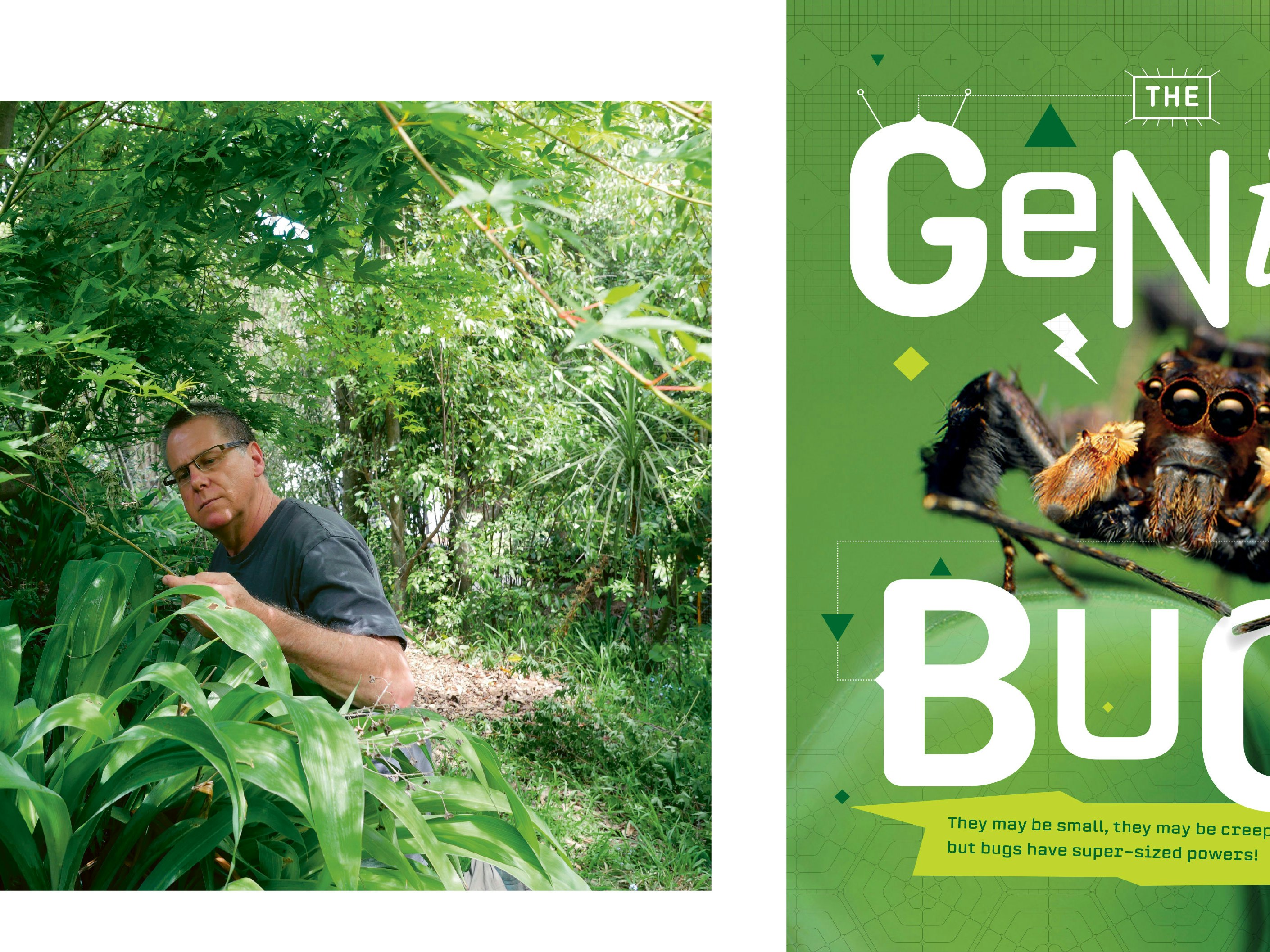

Simon Pollard, author of Why is That Lake So Blue?, discusses his work with Te Papa Press

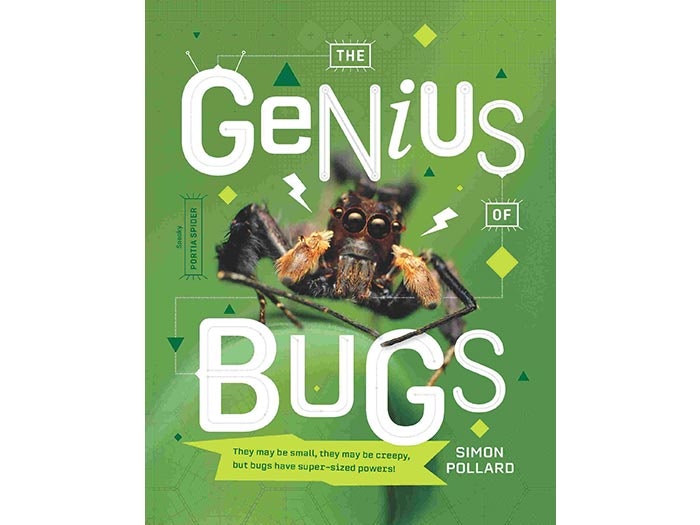

Dr Simon Pollard is a spider biologist and award-winning natural history photographer and writer. He has written and illustrated a number of children’s books in New Zealand and the United States and has twice won the LIANZA Elsie Locke non-fiction book of the year. In 2017 his book for Te Papa Press, The Genius of Bugs, was shortlisted for the New Zealand Book Awards for Children and Young Adults. Simon has also been an advisor, scriptwriter and presenter on a number of natural history documentaries, including the BBC’s Planet Earth. In 2007 he was awarded the New Zealand Association of Scientists’ Science Communicator of the Year Award. Since 2009, Simon has been Adjunct Professor of Science Communication at the University of Canterbury.

It’s been part of my life for around a year and a half, and I have loved researching and writing about Aotearoa’s geology, geography and biology. While I have written articles for adults for decades, I think I enjoy writing for younger readers the most. Since the book is now finished, it feels bittersweet as it is done and dusted. But I have learnt a lot about the country I live in, and appreciate it even more than I used to. I hope readers will gain a similar appreciation for where they live. Because I have worked with excellent editors at Te Papa Press, and because this is a big book, I feel I have really developed my skills as a writer.

I feel very proud of it. Although I wrote the words, the fantastic team at Te Papa Press designed the look of the book. So, I think all those involved in the project should feel very proud of what we have created.

I hope it will give them a sense of the magic of the country they live in, both in terms of how the country came to be, and the animals and plants who live in it. I also wanted the book to be fun. I think sometimes the ten-year-old I once was takes over the writing, and makes bad puns and comments that I would have thought were funny when I was young. I hope I’m not the only one who finds them funny! I also hope they like the fun facts and short stories that are part of each chapter.

This really surprised me. Based on recent genetic studies, the closest relative of the kiwi is not the moa, but the extinct elephant bird from Madagascar. Apparently, they shared an ancestor in Antarctica millions of years ago. That is a very surprising family tree. At that time, Antarctica was a subtropical paradise, rather than a frozen continent.

Wingless bat flies make a screaming sound like a dentist’s drill to scare off lesser short-tailed bats and stop them from stepping on their maggots as they develop in a bat fly nursery within the bat roost. The flies feed on bat poo and raise their young in the roost.

I think my favourite would have to be glowworm larvae. While people marvel at the lightshow they create in caves, it’s a lightshow with a dark underbelly. The larvae have glowing bums to attract flying insects who think they are flying towards daylight. The sticky threads that hang beneath the sinister night-light seal their fate. Apparently, if the larvae have nests too close to each other they fight and this makes them glow even brighter. And one may actually eat the other. I can just imagine a successful cannibal chomping on its dimming neighbour as it sings that old Monty Python song, ‘Always look on the bright side of life’.

I would have to say the life cycle of the long-finned eel. After spending decades in freshwater in New Zealand they swim out to sea, and in the deep waters around Tonga they mate and die. It is not the ending to a Pacific holiday most of us would want. Ocean currents carry the tiny larvae back to New Zealand and after growing into small eels in estuaries they travel upstream just like their mums and dads did. When I was halfway through writing the book, and had just finished writing about long-finned eels, I went down to the Avon River and fed long-finned eels living in their new homes that were made after the earthquakes.

I have always been optimistic, and while we have lost a lot, there are a lot of success stories about saving species. Aotearoa has always had its iconic species, but we are also more aware of protecting the lesser-known species that live here. We are lucky we have so many offshore islands as many are pest-free, or have become pest-free, and are vital refuges for many species. It is amazing to think there are parts of this country where native flora and fauna can now live more or less like they did before people and the pest species they brought here changed their lives forever.

I am very focused when I am writing and spend a lot of time thinking and reading before starting to write. If I don’t understand something, I do not feel comfortable writing about it. So, it was quite the learning curve for a lot of the material in the book. I love writing and I get into a zone where I write to the audience the book is for. As far as deadlines, I write best under pressure and get even more focused to get it finished. I also need a hook to start the chapter or article I am writing. One of the hooks for this book was the kiwi and the giant elephant bird being closely related. You could not make that stuff up! It was also very important to me that each of the eight chapters of the book were equally strong. All the chapters could have been books on their own, so it was writing with the constraints of a word count to get across the essence of what each chapter was about.

I read a lot of science news online and often read the original research papers to get my head around some of the startling discoveries that seem to be made each week. I certainly did a lot of this while researching the book. I am also reading a book on the secret life of flies, as well as one on the making of 2001: A Space Odyssey, which was written to commemorate the film’s fiftieth anniversary. Researching glowworms also led me to another book, How we lived then by Norman Longmate, which is about civilian life in the UK during WW2. I read somewhere that when the light on her bicycle stopped working a woman used glowworms on a make-up mirror to get home in darkness, and when I found out the story was in this book I bought it. It’s a fascinating and frightening book.

A fascinating, fun and engaging book on New Zealand’s amazing natural world

They may be small, they may be creepy, but bugs have super-sized powers!

Simon Pollard, author of The Genius of Bugs, discusses his work with Te Papa Press.