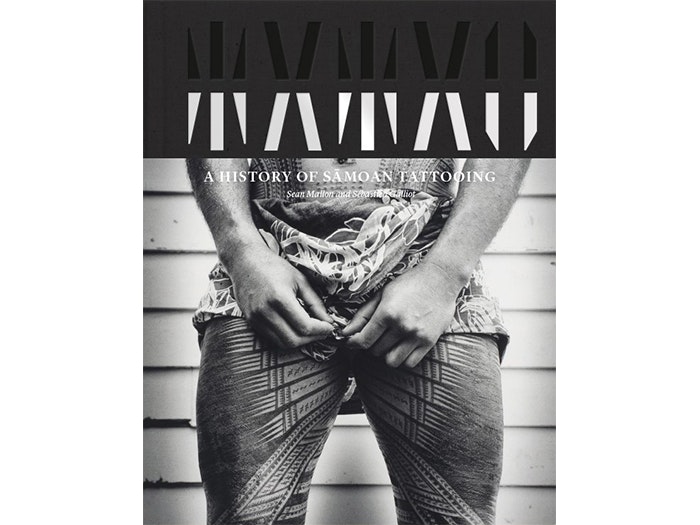

Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing

A beautifully designed and richly illustrated retelling of the unique and powerful history of Sāmoan tattooing, from 3,000 years ago to modern practices.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Sean Mallon and Sébastien Galliot discuss Tatau: A history of Sāmoan Tattooing with Te Papa Press.

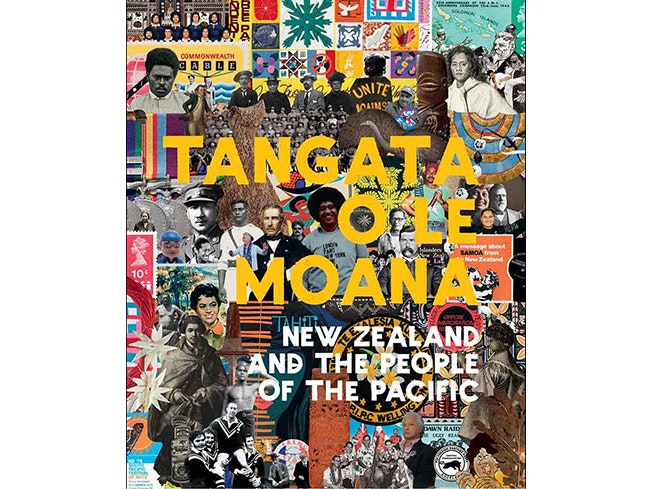

Sean Mallon, of Sāmoan (Mulivai, Safata) and Irish descent, is Senior Curator Pacific Cultures at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. He is a co-author of both Tangata o le Moana: The story of New Zealand and the people of the Pacific (Te Papa Press, 2012) and Art in Oceania: A new history (2012), which was awarded the Authors’ Club’s Art Book Prize. He has been a council member of The Polynesian Society since 2008.

Sébastien Galliot is a French anthropologist associated with the Centre for Research and Documentation on Oceania in Marseille, and since 2001 has made several field trips to Sāmoa, Tonga and Fiji. A photographer and filmmaker, he has published on Pacific and Sāmoan tattooing and co-curated the Tattoo exhibition that toured to Paris, Toronto, Chicago and Los Angeles.

SM: It is a relief that the book is complete and off to the printers. I am feeling some nervousness as we wait for the first copies to arrive, and think about releasing the book to the public and the reception it will get.

SG: I feel like I am ready to carry on the work and use the resources that we haven’t used for this book.

SM: We have worked hard over many years to bring these stories, this history together. There is a pile of stories and images we had to leave on the cutting room floor, so to speak, but what we have ended up with is a piece of work that both of us can stand behind.

SG: Sure! I am proud and happy that we managed to bring this project to a beautiful end. This would not have been possible without Sean and the work of Te Papa Press staff.

SM: This book is the first to cover the 3,000-year history of Sāmoan tattooing. Previous studies have been mainly ethnographic snapshots, or studies made at particular points in time, including a cluster of studies from the late 1800s to the mid-twentieth century. This study analyses and synthesises many accounts of tattooing in their historical context, so we can understand how they were part of larger processes of continuity and change. In general, there are no studies of indigenous tattooing from the Pacific that have the breadth and scope of this book, and none that focus on Sāmoa.

SG: I think this book brings some unprecedented and detailed insights into the contemporary ethnography of the craft, as well as its history and its interpretation as a pre-Christian religious practice. We also have been very careful to provide a broad scope to the study of Sāmoan tattooing and avoiding an hagiographic approach.

SM: I am of Sāmoan descent, so tatau provides me with a way into Sāmoan society, its history and culture. This topic has helped me develop an understanding of the bigger picture, about the histories and experiences of my ancestors.

Tatau is a medium and a set of cultural practices with a high profile, through which I can explore (and hopefully say interesting things about) other topics like power, gender, identity, colonialism, appropriation, globalisation etc. That’s what keeps me interested. I have not invested my time in trying to pin down the meaning of every line or design in tatau, but rather in understanding how people utilise Sāmoan tattooing in their lives, how they put it to use socially and culturally.

SG: Researching Sāmoan tattooing was a teenage dream that I realised by studying ethnology and anthropology at university. When I started making connections between the ethnographic work that I undertook in Sāmoa and in New Zealand, Sāmoan tattooing revealed its anthropological potential. Let me explain that a little bit further. The transnational aspect of this ritual, its continuity through time and its process of transmission are quite peculiar and represent a very powerful case to understand key anthropological concerns, such as globalisation in the Pacific – ritual transmission, for example. That is mainly why I kept on researching. Also because, Sāmoan tattooing is a living tradition, not one that ethnographers are trying to document before it dies. In fact, Sāmoan tattooing moves faster than we are able to record it.

SM: I learnt that the first commercial tattooing premises in Sāmoa was operating in 1896, and according to newspaper advertisements at the time, it offered Japanese-style tattooing. This may not appear to be a big deal to most people, but it helped us to see how the history of tattooing in Sāmoa was not just a history of Sāmoan tattooing, but rather encompassed a number of tattooing practices … there are other interesting stories in the book that illustrate this point further.

SG: I learnt patience (I am joking). Although it hasn’t been published because we found out more information after the book was written, the story behind Jack Groves’ drawings is fascinating. I did not have any time to devote to him during my PhD thesis, and I am glad that we still have a lot to dig through.

SM: We came across drawings made in the 1950s by Englishman Jack Groves, which shows the incorporation of an eagle within the design of a Sāmoan male tatau. One of the stereotypes of Sāmoan tattooing is that it has been passed on, unchanged, through time. Groves’s drawing is visual evidence of how tatau has been a dynamic, changing art form, and that tattooists were inspired by the outside world and creative in their responses to it.

SG: I love Greg Semu and Mark Adams’ photographic work, but I already knew their work. One image that I discovered and really enjoyed is the photograph of the wrestler Peter Maivia.

SM: Tatau is generally surrounded by a spirt of generosity and trust, because the tattooing operation itself is intimate, and involves a fair amount of pain and, of course, permanently marking the body. Tattooists have to be good at managing people and relationships, and from our point of view as researchers, they have been great to deal with.

We have benefitted from the generosity and goodwill of so many people in the development of this project, and I guess this is why it has taken so much time to complete. The book is based on a long list of relationships, for me some of them go back to my childhood, while others have developed in my professional capacity as a curator and researcher since the mid-1990s. The book is a collaborative work, where a great number of people have shared their views or insights about tatau, where photographers and artists have allowed us to use their work to bring the history to life and tattooed people have talked about what it means to be tattooed. We have also benefitted from the vision and generosity of the publisher and designers who have pushed beyond our initial ambitions to create a beautiful and comprehensive, if not encyclopaedic book.

SG: I think before generosity there is a group of researchers, historians and journalists who are filled with passion. I also think tatau is surrounded by a spirit of commitment, perseverance and what we say in Sāmoa loto alofa.

SM: Tatau is a powerful and distinctive looking set of body markings that give Sāmoans a rich resource to pin their sense of cultural identity to. The process of using indigenous tools is also distinctive, and a major attraction for clients, which is probably why it has persisted for so long despite the availability of mechanised techniques.

SG: One thing that is very hard to understand for people who didn’t live in the Sāmoan community is the very specific and specialised craft of the tatau. You can’t just pick up some tools and start playing around with it. The process of learning is long and painful – as is the process of being tattooed. And the cultural value for Sāmoans relies on this very specificity. At least that is my point of view. Sāmoan tattooists are the most skilled hand tapping experts in the world, in terms of rapidity, body coverage and complexity of the whole iconographic assemblage. This is what makes it powerful among and beyond the Sāmoan community.

SM: Writing a book like this doesn’t fit within a day job. In fact it is not a day job, more like an after-hours, late-night-and-weekends job. I’m not complaining though, because researching and writing about history and culture is one of my passions, and it is also a privilege in some ways to have the opportunity to do so. I have been fortunate that my workplace offers time, resources and other important support that helps make a book like this happen. When the going gets tough, it is the responsibility you feel towards the people you have interviewed, and the need to make good on the hours away from friends and family while researching and writing, that keeps you moving toward completion.

SG: Well, I devoted a large part of my previous research positions to studying Sāmoan tattooing. I have been lucky. But in the last few years, teaching at the university took up all of my time, and to finalise the book, I spent the entire last summer working on it.

I put a lot of trust in the collaboration I had with Sean, and I knew that it would eventually end up as a publication. What I didn’t expect was how beautiful the final product would be.

SM: For work, I am reading Museums, Heritage and Indigenous Voice by Briony Onciul, because I am interested in how we can make museums more useful spaces for indigenous people. For pleasure, I’m reading The Diary of a Bookseller by Shaun Bythell, which is about a secondhand bookshop in Scotland. Like a tattooing studio, I suspect a lot can go on in a secondhand bookshop … I am curious.

SG: I holidayed in Romania last month, I brought only one book: Baltimore by David Simon. It is basically the detailed life of a police department in Baltimore. Fascinating because I wish I could write my ethnography with the same talent and fluidity.

A beautifully designed and richly illustrated retelling of the unique and powerful history of Sāmoan tattooing, from 3,000 years ago to modern practices.

Discover a millennium of exploration, encounter, and cultural exchange in this beautifully illustrated history of Pacific peoples in New Zealand.