Tatau: Sāmoan Tattoo, New Zealand Art, Global Culture

The story of Sāmoan tattoo art and the work of Su‘a Sulu‘ape Paulo II.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

The Ten-Question Q&A with the authors of Tatau: Samoan Tattoo, New Zealand Art, Global Culture.

Mark Adams, Sean Mallon (photo by Yoan Jolly), Peter Brunt, and Nicholas Thomas (photo by Annie Coombes). Photos courtesy of the authors.

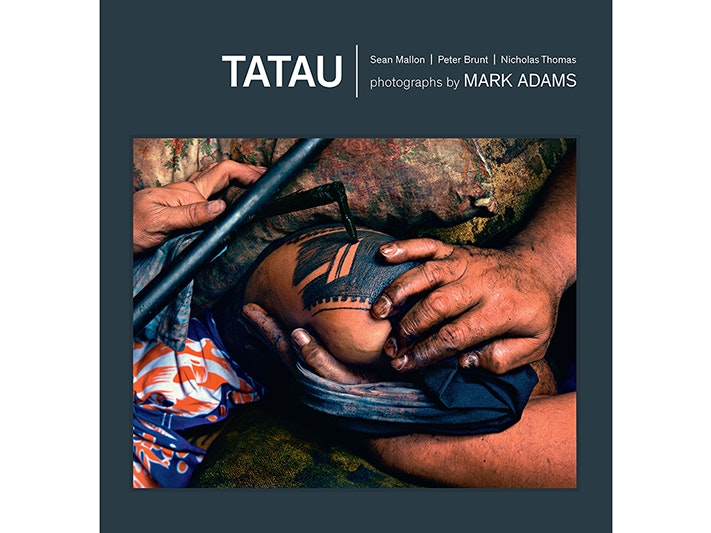

Mark Adams is one of Aotearoa New Zealand’s foremost documentary photographers. His work has been extensively exhibited in Aotearoa, Australia, South Africa, and Europe and at Brazil’s São Paulo biennale.

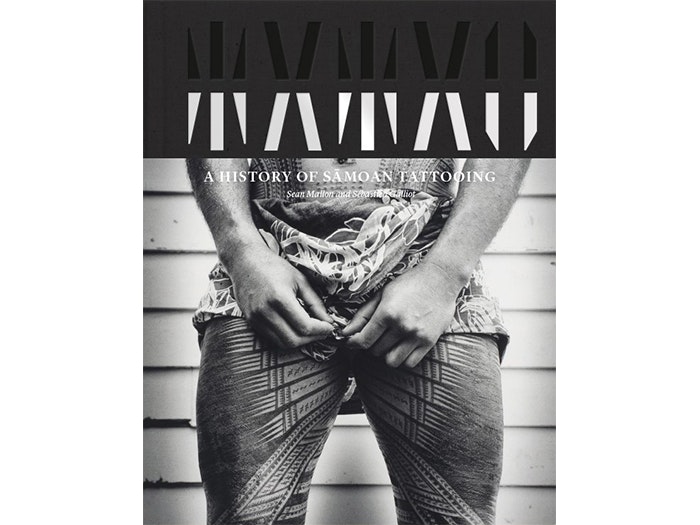

Sean Mallon is of Sāmoan (Iva and Mulivai, Safata) and Irish (Belfast) descent. He is Senior Curator Pacific Cultures at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, where he specialises in the social and cultural history of Pacific peoples in Aotearoa New Zealand. He is the author, with Sébastien Galliot, of the award-winning Tatau: A History of Sāmoan Tattooing (2018).

Peter Brunt is of Sāmoan and English descent, with ancestral connections to Lano, Vaiala and Bedfordshire. He is Associate Professor of Art History at Te Herenga Waka Victoria University of Wellington, where he teaches and researches the visual arts of the Pacific, focusing on the role of art in mediating cross-cultural encounters.

Nicholas Thomas is Professor of Historical Anthropology and Director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at the University of Cambridge. His most recent book is Voyagers: the settlement of the Pacific (2020).

MA: Yes, it does. The production of the first edition was flawed. The reproduction files needed to be improved and I wanted a properly sorted, hardback, weighty tome containing all this memory to leave behind.

NT: Tatau is the definitive publication of an art project that has been genuinely unique, that has documented a remarkable cultural history. If we’re now more accustomed to the idea that local traditions can have big impacts, such possibilities were inconceivable when the earliest of the photographs in this book were taken – it was then assumed that the march of modernisation and globalisation towards consumerist standardisation was unstoppable.

NT: Mark Adams’ images revealed that an ancestral body art could not only be sustained, but also develop and cross borders in a diasporic setting; what happened subsequently, and what later photographs documented, was tatau’s extraordinary global impact, which has continued, as Sean Mallon demonstrates.

And that’s only half the story. Somehow Sulu‘ape encountered the photographer who could do his practice, and this history, justice. Mark Adams’ commitment to what he calls ‘context’, and his mastery of large-format photography were somehow right and necessary for this project. If anything, the book is more salient to global debate about place, culture and difference than it was at the time of first publication, and it is brilliant that the larger format and expanded edition appears now.

PB: For me, they document a cultural and historical transformation taking place in the Sāmoan diaspora, New Zealand society, and tatau as a form of global culture. But the power of his photographs also lies in their aesthetics, their ethics and their historical and cultural acumen. Some of the photographs in Tatau are visceral with blood, swollen flesh and bodies in pain. They capture the depth of who we are as physical sentient beings at the same time as the body is being culturally marked in very specific ways.

They also reflect Mark’s respect for his subjects – the people and places he documents. But that respect is as much an aesthetic as an ethic; it comes through in the way he sees, chooses, frames and takes his pictures. Historical consciousness is also at the centre of his work: history remembered, and history being made. I think the re-issue of the book more than two decades after its first publication will be very interesting in that regard.

MA: Dr John Dunn decided to get his pe‘a and it was mooted that I do some photographs. I went to visit John. In the living room were some paintings I knew, including a very familiar Christ by Tony Fomison that was always on the wall at Tony’s place. That decided it.

SM: It focusses on the questions that motivated Mark’s tatau photography and the relevance of those questions (and his photography) to Sāmoan photographers and image makers since the first edition of the book.

MA: The picture of Tom Ah Fook in Triangle Road is the first successful attempt where the large format colour transparency and the electronic flash lighting balanced with daylight natural light applied to a fluid social situation actually worked at all levels. It allowed the image depth of field and high-resolution combination of portrait and interior context combined with the freezing of movement only normally achieved by small format cameras.

PB: My favourite is the picture of the evening of the umusaga for Fuimaono Norman Tuiasau. For me it captures history in a portrait. Specifically, a portrait of the kind of cross-cultural friendships and alliances that were transforming New Zealand society in the late 1970s and early 1980s.

MA: Artists, that is real artists, are easily recognisable regardless of what age of the world or culture they operate in. I don’t accept that this is a western imperialist conceit. Artists are all insufferable egotists regardless of whether they are notionally servants of an elite in Florence or a district in Savai‘i or Upolu or South Auckland for that matter.

Paul was not just a village craftsman serving matai and Sāmoans alone although he did that exhaustively. He pushed the envelope with increasing formal elegance and complexity and his practice into a global context.

MA: He was a one-off.

SM: Arguably, the place of tatau in the fa‘asāmoa is as powerful and important as it ever has been for Sāmoan people. The difference is that it is more visible today through mass media, and the conversations around its production and cultural significance are more widespread. More than a decade later, this second edition of the book introduces this body of work to much larger and increasingly connected audiences.

MA: My hope for the photographs is that they can help us with our remembering.

PB: I hope people will appreciate the extraordinary power of Mark’s work and see Tatau in relation to his oeuvre as a whole.

The story of Sāmoan tattoo art and the work of Su‘a Sulu‘ape Paulo II.

A beautifully designed and richly illustrated retelling of the unique and powerful history of Sāmoan tattooing, from 3,000 years ago to modern practices.