Drag in 1970s New Zealand

In this excerpt from Mates & Lovers, Chris Brickell explores the vibrant world of drag culture in New Zealand, when drag ‘jumped off the stage and into the streets’.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Lauren Lysaght’s mixed media work Hidden Agender is inspired by the life of Eugenia Falleni (about 1875–1938), a woman who presented herself as man in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and whose life was placed under the microscope in 1920 when she was charged with murder and ‘sex fraud’.

Eugenia Falleni, alias Harry Crawford, special photograph number 234, Central Police Station Sydney, 1920, 1920 Photo by New South Wales. Police Dept. and courtesy of NSW Police Forensic Photography Archive, Justice and Police Museum, Sydney Living Museum

Eugenia Falleni moved with her family from Italy to New Zealand in 1877, where they settled in Newtown, Wellington. Lauren Lysaght’s grandmother – Nita Gini – told her that Eugenia’s nickname was ‘Tallyhoe’ because she ‘swaggered’ about Newtown dressed as a man.

In the late 1890s, Eugenia moved to Sydney, where she gave birth to a daughter, and subsequently presented herself to the world as ‘Harry Leo Crawford’. In 1913, Harry married Annie Birkett, and the couple opened a confectionary store in Balmain.

In 1917 Annie mysteriously disappeared. In July 1920 Harry, who had remarried, was arrested for Annie's murder. While Eugenia appeared at the preliminary hearing dressed in men’s clothing, she attended the trial in women’s clothing. The Crown accused Eugenia of perpetrating ‘sex fraud’ and of murdering Annie in order to cover up her crime.

What became known as the ‘man-woman’ case made headlines in both Australia and New Zealand.

Although convicted and sentenced to death, Eugenia was released in 1931 on the grounds of ill health. She continued to live in Sydney as ‘Jean Ford’ until her death in 1938, following an accident with a motorcar.

As her biographer Carolyn Strange has written, speculation about Falleni’s identity and guilt has continued well beyond her death

At her 1920 trial her daughter had testified: ‘My mother has always gone about dressed as a man’.

Since then doctors, psychiatrists, journalists, endocrinologists, feminists, playwrights, film makers and historians have tried to make sense of Falleni. They have labelled her variously as a sexual hermaphrodite, a homosexualist, a masquerader, a person with misplaced atoms, a sex pervert, a passing woman, a transgendered man, and as gender dysphoric.

Falleni proclaimed her innocence of the murder but never explained what induced her to live as a man.

[1]

Lauren Lysaght has her own thoughts on the matter. When she first exhibited Hidden Agender in 1993, she wrote the following challenge for viewers in collaboration with curator Michael Eyes:

‘On a trip to Italy recently I discovered I am a blood relative of Eugenia Falleni.

For most of her adult life Eugenia lived as a man. In 1920, Sydney, Australia she went on trial for the alleged murder of her first wife.

The extraordinary circumstances of the trial lead the media to dub it the ‘man-woman’ case. Although the evidence was inconclusive Eugenia received the death sentence (later it was commuted to a life sentence and then she was released).

I believe Eugenia went on trial primarily for living as a man, and now as her relative, I am reclaiming her through this work.

As you look at the work, how can you answer these questions:

1. What was on trial?

2. Were the authorities, the media, the public confused by or entertained, or vengeful about the ‘man-woman’ case? Was Eugenia a specimen?

3. Why was it so easy for her to be a self-made man?

4. Was heterosexual ignorance Eugenia’s bliss – for a while?

5. Wouldn’t you want to have your breakfast cooked for you every day? Wouldn’t you want a wife – especially if you are a woman?

6. Eugenia’s wives defended her manhood and their femininity – were none of them queer?

7. While Eugenia was in prison she was ‘corrected’. What corrective practices do you enforce?

8. Living as a man did Eugenia know more about society than society knew (or wanted to know) about itself?

Read more about Eugenia Falleni’s court case

Read more about Eugenia Falleni’s life

1. Carolyn Strange, ‘Falleni, Eugenia (1875–1938)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/falleni-eugenia-12911/text23325, published first in hardcopy 2005, accessed online 3 December 2019.

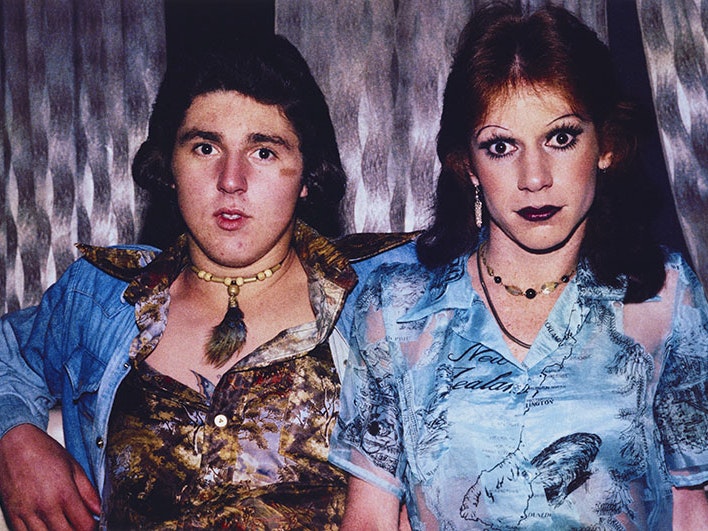

In this excerpt from Mates & Lovers, Chris Brickell explores the vibrant world of drag culture in New Zealand, when drag ‘jumped off the stage and into the streets’.

Fiona Clark is one of New Zealand’s most celebrated art photographers. In this essay, she recalls her time as an art student in Auckland in the early 1970s, when she began to take photographs of the people and the night life around her.