Collection ledgers

William Ockleford Oldman was a trader and collector of ethnographic objects from countries around the world including the Pacific. Read his handwritten records in his registers.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Artist and activist Luisa Tora shares the story of a treasured salusalu (necklace) and its intrinsic connection with her matavuvale (family).

Luisa Tora, with her salusalu. Photo by Sangeeta Singh, courtesy of Luisa Tora

I write this post as we mark the sixth anniversary of my father Vatiliai Kalinivetau Tora’s passing. I wore this stained salusalu for him at my graduation from Manukau Institute of Technology’s Faculty of Visual Arts in May 2015.

The graduation ceremony fell on what would have been his 67th birthday, three months after he had died. Traditionally, this is when the Fijian mourning period is lifted in a bogidrau (100 nights) gathering and ceremony. It was made even more bittersweet a graduation as my younger sister Talei and I had hoped to bring him to Aotearoa for it.

My longtime homebody father had resisted any suggestions about travel as always but I still wanted to celebrate him on the day. My sister offered to bring my graduation salusalu with her from Viti and I asked her to commission this stained version. Salusalu are usually made with fresh flowers and scented leaves, this one is made with vau.

In the excitement of the transfer and my eternal embarrassment we lost the note with the maker’s name on it. My sister found her at the Suva Flea Market where many Suva-based Vitians shop for Vitian iyau. Talei says the woman was puzzled by the request but was happy to fulfill it. My sister explained the reason for the curious tribute adding “she’s an artist”, which probably didn’t make things any clearer.

This is not the first time my parents and I have crossed paths and planes. I received my Aotearoa permanent residency on the anniversary of my mother Maca Baleikasavu (nee Vulakouvaki)’s June 11 passing. My late mentor Dr Teresia Teaiwa said that my parents and I are “numerologically connected”. We remain bonded in death as we were in life.

The same goes for my parents. You couldn’t talk about ‘Mac’ without talking about ‘Tilly’ or ‘Mr T’ without ‘Mrs T’. They opened their hearts and home to uncountable LGBTQIA+ whānau and played host to an array of artists, poets, and activists. Many of these people would regularly see my parents serenade and dance with each other in the kitchen.

As a 20-something-year-old, Dad had played drums for the rock band, Maroque 5. My grandfather, Alifereti Tora, was a talatala at the Assemblies of God’s Calvary Temple and my grandmother, Joana (nee Tabua), was a matron at Tamavua Hospital, so I’ve often wondered how that conversation played out. In their own kitchen Dad would sing Black Magic Woman to my mother, and she in turn would sing Son of a Preacher Man to him.

Dad preferred a quiet night at home with a cold beer over any social event we invited him to. You could always rely on him for a good talanoa on the porch about politics, music, and Viti's evolving national landscape. He might strum a guitar and sing us some Billy Ocean or Engelburt Humperdinck and take much pleasure in naming the samples in pop music.

His dry quips and strange theories kept us amused and intrigued; “You would make a good lawyer because lawyers get to sleep a lot.” He always ended his phone calls with, “Cover your chest and eat your vegetables.” One time, he surprised my partner and I when he agreed to attend an LGBTQIA+ fundraiser with us. As we watched our friends perform, we heard a couple next to us making derogatory remarks about the performers. My Dad turned to them and quietly said, “We came here to enjoy ourselves. If you don’t like it, you can leave.” You could have knocked us over with a feather.

This is why I chose this salusalu to share with you. This salusalu is a touchstone for my father. It celebrates him and marks the traditional lifting of the mourning period following his death.

Vitian iyau (including masi, mats, and this salusalu) and its production and exchange are central to Vitian cultural and social life.

Iyau is usually made for a particular task with the goal of building or maintaining relationships. The skill of the maker and the well-finished object demonstrate how much you value the recipient. The wealth of the iyau exists in its transfer between people. Salusalu have a shorter shelf life as they are gifted to people at celebratory ceremonies like graduations and weddings.

My family would keep freshly-made salusalu until the flowers and leaves dried but the scent of uci lingered on. I feel like my father and mother were never mine alone. Their hearts and home were too big for this.

I share this salusalu with you bearing this in mind. Stay well. Love the one you’re with. Cover your chest and eat your vegetables.

Salusalu (neck wreath), 2000s, Fiji, maker unknown. Gift of Kelera Uluiviti, 2011. Te Papa (FE012530)

William Ockleford Oldman was a trader and collector of ethnographic objects from countries around the world including the Pacific. Read his handwritten records in his registers.

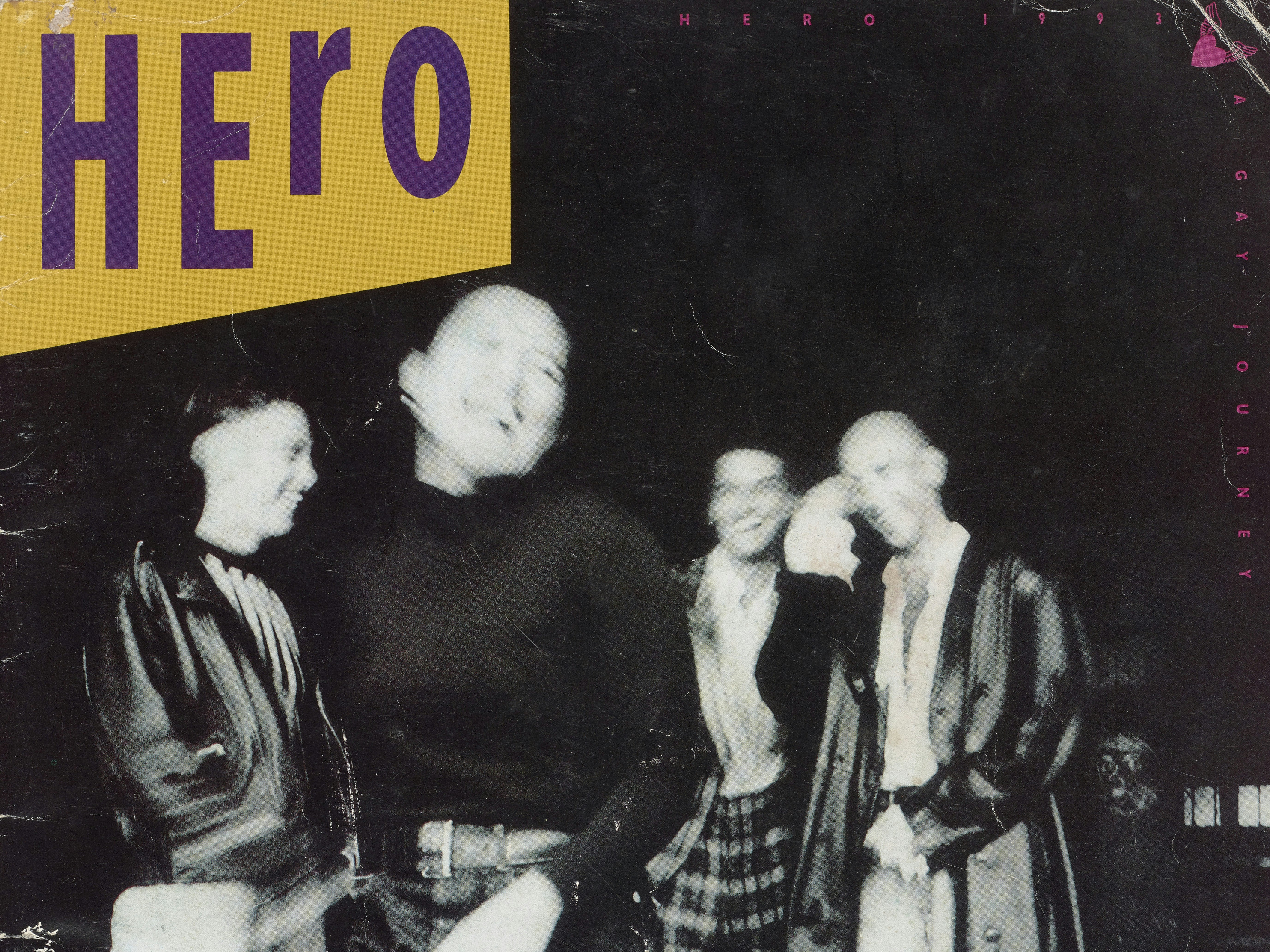

‘I, a Sāmoan gay, queer man came to know myself as not quite Pacific enough or not qwhite queer enough to be considered a central concern.’ Seuta‘afili Dr Patrick Thomsen reflects on his coming-of-age in Queen City.

Tai Paitai reflects on people, places and a particular time in his life, post the Homosexual Law Reform Bill.