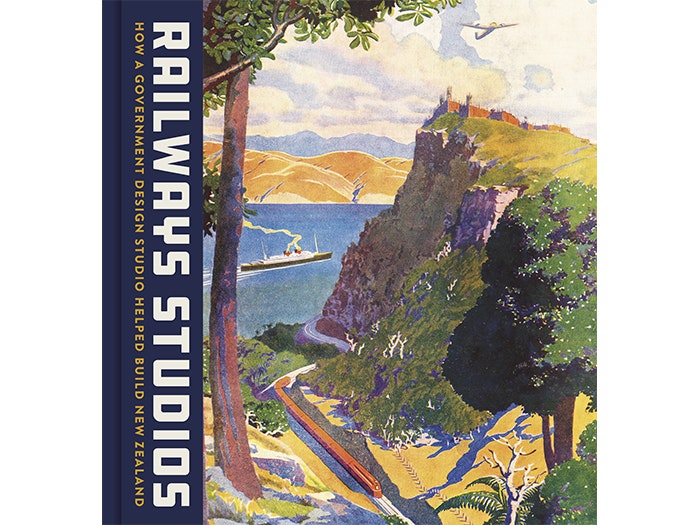

Railways Studios: How a Government Design Studio Helped Build New Zealand

A definitive illustrated history of the graphic work of the railways studios.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Peter Alsop discusses Railway Studios: How a government design studio helped build New Zealand with Te Papa Press

Peter Alsop is a senior executive who has worked across the public and private sectors. He is a keen collector of New Zealand art, with particular interests in tourism publicity, hand-coloured photography and mid-century New Zealand landscape paintings. He is the author and co-author of six previous books, including Promoting Prosperity, Hand-Coloured New Zealand and Scenic Playground.

This is one of New Zealand’s greatest design legacies, with both artistic and social significance. 100 years on from the Studios’ start, it was high time to recognise the work.

As a collector, there’s no bad time to collect! For a book project like this, with one shot to get it right, the hunt for the best imagery – and research for that matter – is always on. Despite planning ahead, there is always something of value that pops up late in the piece.

Yes, the role of the railways in driving both economic and social prosperity – such as through the trading and social connections rail enabled (including tourism) – is now overlooked. The Studios were the advertisers and promoters of rail and, alongside, dominated the ‘gallery of the street’ by designing posters and billboards for commercial clients. When the Studios started, advertising itself was also just blossoming as a commercial activity, so the Studios were at the heart of major changes in social and commercial norms.

This nexus was trumpeted at the time: art as a pathway to better business, because of its centrality to alluring advertising (‘commercial art’). In principle this hasn’t changed, but now the forms and mediums of art in advertising are typically very different – and mostly digital. Hand-drawn and hand-painted illustrations within advertising left the market long ago.

All of our contributions were multi-faceted and collaborative, so it’s hard to boil things down. In short, though, Neill is a fantastic historian and brought deep knowledge of rail and social history – and therefore passion – for this cause. Richard and I brought deep knowledge of New Zealand’s early commercial art, with me also curating the book’s imagery. Katherine is a fantastic researcher and led the biography work – a lovely part of the book – and she’s just one of those amazing people who does whatever needs doing. We all, though, crossed over on everything; from many hands and perspectives comes better work. Others, too, made substantial contributions, particularly Gary Stewart on co-design and production, and research assistants who were instrumental to building our extensive research archive.

Yes, a nice and unexpected result. The beautiful stained glass windows in the station were installed in 1906, and since then the designer has remained unknown. Through our research, we’re now very sure they’re the work of Adam Howitt, whose work turned up by surprise in an old unmarked satchel we almost overlooked. He was a draughtsman but, with time, we can now judge his work – such as logos, invitations and insignia – as very early examples of New Zealand graphic design (though long before the label ‘graphic design’ was coined).

Barry Ellis, now 83, who I‘m lucky to count as a friend. He has been inspirational in his love of art, and in helping give me a closer understanding of Studios life. The book’s genesis was a cup of coffee with Barry in 2013, and it has taken seven years to get the job done. I hope Barry likes the book! Alongside Barry, artists Alan Love, John Anstiss, Graham Winter and Ray Allen have also been a huge help. Other Studios artists – like Sid Wiberg, Maurice Poulton, Ted Lawn and Stanley Davis – are central to the story but have long passed on.

Just one? I’ll take New Century Salt from around 1948, a poster using cascading tins of salt in a very simplified graphic style. It’s reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s soup cans but designed over 10 years before. The product – salt – is also a reminder of the liberal use of glamorous commercial art given the prevailing hype around ‘art-industry-commerce’ and the outdoor advertising craze.

Other than my wife wanting my night-time book work to end?! (This book was immensely challenging.) For me, the gallery spreads in this book are much more diverse and adventurous in their composition than my previous projects. They look easily done, but they were very demanding to get right. Gary Stewart’s finesse was immensely useful. The lesson, though, is that the toil is worthwhile – visual variety is, I think, the spice of life. But let’s see what readers think!

That important legacies come from unexpected places. This is the story of an in-house unit of a government department selling services to commercial clients and dominating the ‘gallery of the street’. This would beggar belief today, but it did actually happen – and New Zealand is the richer for it.

A definitive illustrated history of the graphic work of the railways studios.

Peter Alsop, Dave Bamford and Lee Davidson, authors of Scenic Playground, discuss their work with Te Papa Press