E te whānau, we’re nearing the end of the series, and Khali’s whakaaro turn towards all the ways our taonga might be brought home, to Aotearoa, and to their communities.

Khali meets up with Amber Aranui, a researcher and a kaimahi at Te Papa in the repatriation team. Reflecting on that early history of how taonga end up in museums, Amber and Khali discuss the repatriation and reconnection of taonga Māori with iwi Māori.

Amber has the hard job of finding those connections, a job that often feels like detective work. It also means a lot of time overseas, and confronting all the horrific ways colonialism has lead to taonga and tīpuna being held in collections overseas.

“So for the vast majority of tūpuna that are located overseas that we bring home, they were stolen. Plain and simple. Obtained without consent and a lot of times, under the cover of darkness behind the backs of communities that scientists or naturalists had befriended, under the guise of studying the natural flora and fauna of a place.” – Amber Aranui

She shares some tips on how we can find and reconnect with our taonga and tīpuna. She talks about her personal aspirations for her mahi.

CONTENT WARNING: This episode discusses the theft and repatriation of the bones of real ancestors. The topic is a painful one, and may be upsetting to viewers. If you choose to watch, please take care.

– Director Kahu Kutia

This video is available with subtitles in English (with te reo Māori), and te reo Māori.

Transcript

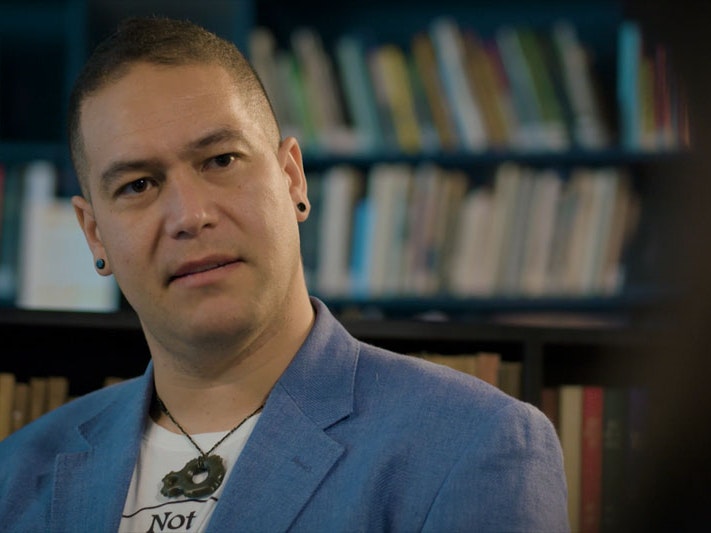

Khali Meari: So far, we’ve been on a journey to understand heaps of the history of our taonga that live in archives and museums.

It’s been such a privilege to see and connect with all of these taonga. To consider their whakapapa and how it connects with our own.

So here we are, back at Te Papa Tongarewa, where in episode one we learnt all about how taonga become a part of our collections here, and today we’re going to meet someone who is an expert in the repatriation or the return of our tīpuna and our taonga back to their people.

Amber Aranui: Ah, ko Amber Aranui ahau, ko Ngāti Kahungungu me Ngāti Tūwharetoa ōku iwi.

I am a curator, a curator Māori, but prior to that, I spent probably the last 14 years as a researcher for the Karanga Aotearoa repatriation programme.

And so our mahi was responsible for bringing our tūpuna that reside, currently reside, overseas and to bring them home, and to bring them back to their people.

If you want to look at repatriation, and really understand kinda what it is from a technical perspective it is, it is the return of something or someone back to their place or country of origin.

And so, within the Te Papa context, it actually is a little bit more than that. And I think for te ao Māori it’s a little bit more than that. And for us it’s about reconciliation, reunification, and reconnection of taonga and tūpuna back with us that live today.

The vast majority of tūpuna that are located overseas that we bring home, you know, they were stolen. Plain and simple: obtained without consent.

And a lot of times, you know, under the cover of darkness. Behind the backs of communities, that scientists or naturalists had befriended, under the guise of, you know, studying the natural flora and fauna of a place. But all the time, they’re sort of going in and finding out where people’s urupā are, burial caves, and just stealing their tūpuna.

And you know, for me, that was quite hard to deal with when I first started this mahi.

It is a hard mahi and it’s quite heavy sometimes, uh, as you can imagine. But actually it’s really rewarding when we see the tūpuna that we’ve worked so hard to bring back from museums overseas – actually go home to their people.

For me, you know, it’s only one part of the journey, is to bring them back here to Te Papa, whether we hold them temporarily so we can finish the research and make sure that we know where home is for them, and then we talk to their people and then arrange for them to be returned.

So for me that’s the most important part of that mahi, is when they go home.

Khali: But there’s a long process to get these taonga home. And a lot of Amber’s work is like detective work.

I ask her to show me some of the resources she uses to find our tūpuna and their taonga origins.

Amber: So these are some registration books, pretty standard for museums. And actually it records some of the taonga that we have. You know, we’ve got quite a number of these and what I like to do, is sort of start off with these registers.

Sometimes these are the first time taonga are entered into the museum. And so, they can have quite a lot of information.

And there are also a lot of other types of information available. We have accession schedules, which is just a piece of paper that when those taonga came in, they filled it out and then the numbers were placed into this book.

So there is a number of ways in which you can look for information.

Papers Past, I think, also is a really good resource, and that is all of our old newspapers of the day.

The Colonial Museum usually had a report, and information around that, around what taonga came in and who gave them, was usually recorded. So you can usually find really good information in that as well.

Khali: So what kinds of advice to you give to hapu, iwi, and whānau who are looking for taonga here in the museum?

Amber: So I think the first step I would do is just to look at what we have online. So we have a large number of taonga that are available to look at online, a lot of them aren’t provenanced. So, you’re kind of looking for a needle in a haystack, but sometimes, you know, there are taonga there that have been identified.

The thing would be to have different place names. Sometimes you might be looking for marae names, names of rivers, names of rangatira.

Khali: And these would all be associated with taonga?

Amber: Yes, they can be. The other thing is probably the most common thing is a collector. So if you know, for instance you had a man that was a really well-known collector, so for instance the Tairāwhiti area, you have the Black Collection, so that would be a place to start.

Try and get an understanding of what is located at other museums that you know of, find out where those collectors are or where they’re associated with. And use that information to come to other museums like Te Papa, to sort of follow up.

[inaudible conversation]

Khali: What drives you to stay here and keep these connections and bring our tūpuna home?

Amber: I think, you know, we have to do it. It’s our responsibility, you know, the museum work is not for everybody but I think it’s important that we have Māori in these spaces, and to help facilitate that reconnection.

For me it’s about enabling iwi, hapu, whānau to reconnect with their taonga and their tūpuna. And, you know, what better people to help do that than their own?

I see the future of museology, particularly for our taonga, is that museums, wherever they are in the world, you know, they relinquish that power, that power of the narrative, where it’s the museum telling the story of the people. Now it’s the people telling the story of the people in the museum space.

And you know, you get the real stories, the rawness that you don’t get from an outsider’s perspective.

And I think that’s the difference, particularly here, you know, people want to come to a museum to learn about people. And what better way to do that, than through the voice of those people, whether it’s through their kōrero, through things like, you know, like kōrero on the wall or video or actually the taonga themselves. They are given that ability to speak again.

And I guess that’s really what mana taonga is about.

Khali: What can be more important than returning our tūpuna and their taonga back to the communities they come from?

I sit with sadness and with grief, for all those still left in the lands faraway, awaiting for an opportunity to reconnect and return home.

And what about us? What else can we explore on our journey together?

No doubt there are millions of things we could talk about. But with one episode left, I think there’s a really important question to be answered.

When our taonga do return home, when our taonga live amongst our people, what does that look like?

How might our tikanga Māori be used with our taonga outside of institutions like Te Papa.

It’s time for us to leave the city, and go on a bit of a haerenga to Te Matau-a-Māui.

Kia mau tonu mai.