Watch: Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho #1: Lost in the Colonisation Machine

Check out some early taonga Māori in Te Papa’s collections and hear how they got to be here. Spoiler alert: It usually wasn’t a good story.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Well e te whānau, here we are at the final episode of this series, Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho, and what a journey it’s been!

In the previous episode, Khali chatted with Amber Aranui about the work of bringing tīpuna and taonga home to Aotearoa, after they’ve been taken overseas.

In this final episode, Khali has one more question. When our taonga are cared for in and amongst the communities that they come from, what does this look like? How is it different from contemporary museum practices? And what tools can whānau use to take taonga care in to their own hands?

We head to Te Matau-a-Māui, to meet up with an old friend of Khali’s, Waitangi Teepa. Waitangi is working at EIT, as a kaihahu mahara, a memory exhumer, with a significant collection of Ngāti Kahungunu manuscripts. She shares some of her whakaaro around kaitiakitanga.

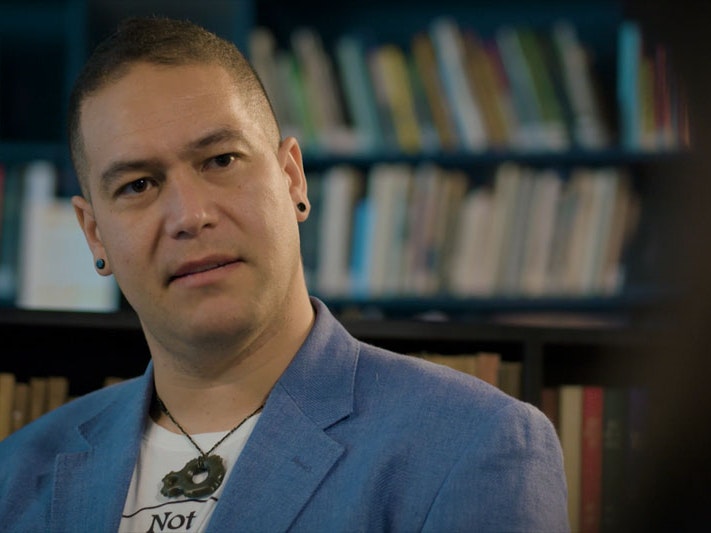

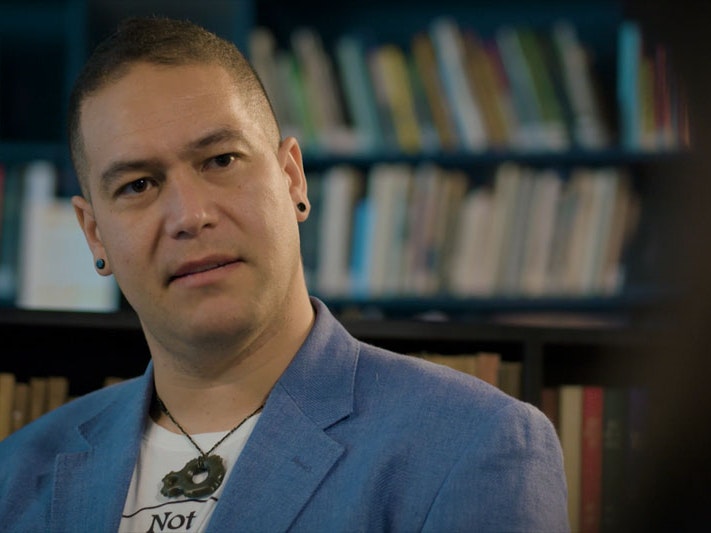

We also meet Dr David Tipene-Leach, a whānau kaitiaki for this collection. Khali asks him what is significant about this collection for him and his whānau.

As we look to the future for our taonga, what are some of the ways we are reconnecting taonga and mātauranga with hapū and iwi? How can we envision care for taonga within a Māori framework? These are some of the things we’re thinking about in this final episode. Khali takes the time to reflect on the journey we’ve taken in this series.

Thanks for joining us along the way. Mauri ora!

– Director Kahu Kutia

This video is available with subtitles in English (with te reo Māori), and te reo Māori.

Khali Meari: What can taonga care look like when it happens amongst our own people? If given the opportunity, the resource, the time, and the skills, how do we want our taonga shared with our people?

Nau mai rā ki tēnei te wahanga whakamutunga mo Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho.

We’re here in Te Matau-a-Māui at the Eastern Institute of Technology, and we’re here to meet a very good friend of mine: Waitangi Teepa.

Waitangi Teepa: Tēna anō koe.

Ko Waitangi Elizabeth Teepa tōku ingoa.

I tipu ake ki roto i te whārua o Ruatoki.

Ko Tūhoe, ko Ngāti Hine, Ko Ngāpuhi ngā iwi.

Ko te ara o tāwhaki tēnei. Tēnei taha te taha wahine. Tēnei taha te taha tāne. Ko tō Kuia tēna, ko Nanny Materoa!

Khali: I pehea tō tau ai ki ēnei momo mahi?

Waitangi: Nā, te hoki whānui atu mātou.

Tuatahi, i roto tāku Aunty i ēnei o ngā mahi. He kaitiaki ia. Ko tana ingoa, ko Hema Temara.

I roa ia e mahi ana, i roto i tēnei wāhanga, te kaitiakitanga, te taonga tuku iho.

Engari, he pērā hoki a Māma rāua ko Pāpā. Ko taku pāpā i heke mai ngā tāngata kaihahu.

So that’s a traditional exhumer. That’s the lines we come off.

I tēnei wā, ka noho au hei kaihahu mahara.

So I specialise in memory exhumation, and that’s part of custodianship, guardianship.

That means I’m the first person that usually goes in and investigates what’s in a box. Most of the taonga we’ve got were in banana boxes or in, they weren’t in very good shape.

Khali: I’m curious to know more about the taonga laid out in front of us.

Covid rules meant that we weren’t able to get into the store rooms to see the originals, but Waitangi Teepa had laid out copies of the letters of the Tipene Matua collection for us to get close to.

Waitangi: Ko ēnei taonga, nō roto mai i tetahi o ngā rōpū e kī anā, Ngā Reta o Hēnare Matua.

So they’re a part of our Tipene Matua whānau collection. And this particular collection that we’ve got, this is the Hēnare Matua letters and manuscripts. They were written by at least, 600 different tīpuna. But they are petitions, and they’re not only land petitions but they are petitions about mākutu, they’re petitions about adultery, about alcoholism. So everything about life.

When I first started, we had problems. Like all taonga, you know, when you get your pounamu for the first time you’ve got to bond with it.

Like all whakawhanaungatanga, I’d go in and I’d be like I’d go into the stackroom and I’ll be like “Mōrena!” and then we’d have conversations.

And everyone would be like “What are you doing?” And I’m like “I’m bonding, I’m bonding with my tīpuna. You fullas have to realise they haven’t seen anybody. I am the first human, living human, they have come across. I am going to give them the manaakitanga that we do as Māori.”

Khali: We’re lucky that one of the whānau kaitiaki of this collection, Dr David Tipene-Leach, also works on campus.

Waitangi Teepa has asked him to come over to share some kōrero about the history of the collection.

Dr David Tipene-Leach: Ko David Tipene-Leach taku ingoa.

Nō Pōrangahau ahau, nō te whānau o Tipene Matua.

Ko ahau tētahi o ngā kaimahi o kōnei o E.I.T.

Koinā.

Yeah well, they have been a hidden collection. I didn’t know they existed until the day that my aunt opened the black box, the tin box. But my uncles did, and my grandfather did but nobody ever spoke about them. So they were obviously passed from, they were written to Hēnare. Tīpene is his younger brother. He kept them. He sent them to Taketake. Taketake sent them to Te Kākaho, down the line. Sent them to his children, they got divided up into three different boxes – parts – and they gave them to me.

Mai rā anō tētahi o aku mahi he pānui i ēnei reta. E tahi o ēnei reta. Ko ētahi e kite atu ana ahau. Ko tēnei nā, ko tēnei waiata. Ko te pai o te waiata, te pai mārika o ēnei kupu, tēnā whakarongo.

“Tēnei ka noho i taku whare hauangi ara rā ki te uru, ko te whare o Tāne, ko te whare tēnā whakarato atu ki runga i te rākau kohukohu o te rangi.”

I think that he’s talking about the repudiation movement. Sitting in a cold space, trying to think about provisioning themselves for the battle that they have ahead. In the same way, “ko te rākau kohukohu o te rangi”.

My understanding of that word is that it is a trap that was set by some of the atua i roto i ngā rangi i runga.

So this waiata has been with me for years, 15, 20 years and has been just one of the joys of my life.

Khali: I’d really love to hear from each of you your thoughts for the future especially when it comes to these manuscripts and these taonga tuku iho.

David: I’d like to tell you what I saw two months ago, when I took a single paper-bound set of 25 letters back – 25 out of the 897 – with a print of the original, and the transcript, back to my uncle – and the light in his eyes and the tears that he shed at the time that he opened this and looked through it.

Koirā ētahi o ngā painga kua puta mai.

We didn’t expect a lot because we’d never had a lot. But actually, in the process we have gotten screeds of reward.

Waitangi: One of my biggest dreams and aspirations for this particular collection is to provide a sample of what whānau can achieve outside of an institute and not only what whānau can achieve but what they can achieve in collaboration with our kaitiaki within the sector, our kaitiaki Māori.

Whānau need to remember that they’ve been kaitiaki since te ōrokohanga o te ao. They have survived with, even if it’s this much knowledge and that knowledge is the story of Ranginui and Papatūānuku, it’s survived more than 200 years. So why are we giving our stuff away to other people when we are more than capable of taking care of it.

Khali: Te hōhonu, te ataahua hoki o ēnei kōrero kaitiaki! E rere ana aku mihi ki te tokorua, me ā rāūa wawata mō ēnei kohinga kōrero. What an inspiring wero to us all as we finish off this series.

Well whānau, here we are at the end of this little haerenga. There’s so many words we could speak in to this kaupapa and still, I feel we have only just scratched the surface.

More than anything, I hope this kaupapa gave you some tools to take with you on your own journey of reconnection.

E tipu e rea mō nga rā o tōu ao.

Kei aku nui, kei aku rahi kua pupū ake te manawa, kua hohou atu tātou ki roto i ngā wānanga kia para te huarahi ki te ao mārama.

Otirā, mai i a mātou o te tīma o Ngā Taonga Tuku Iho ki a koutou.

Mauri ora!

Check out some early taonga Māori in Te Papa’s collections and hear how they got to be here. Spoiler alert: It usually wasn’t a good story.

We meet Keri-Mei Zagrobelna (Te Āti Awa, Te Whānau-a-Apanui), a jewellery maker in Te Whanganui-a-Tara. Keri-Mei talks about her history with the collections at Te Papa, which spans all the way back to the work of her kuia.

Khali meets up with Maimoa Toataua-Wallace, a staff member at Ngā Taonga Sound & Vision. Ngā Taonga is home of audiovisual archiving in Aotearoa. Movies, sound recordings, home videos, television, songs, anything to do with the audiovisual world, you can probably find it here!