War, migration, and change

One item the Pākehā visitors brought caused more upheaval than any other – the musket. At the start of the 19th century, these guns were the norm on European battlefields.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

British and other visitors to New Zealand were quick to realise the business opportunities this land offered. Likewise, Māori saw that the visitors offered new trading possibilities.

Kei a koe te taonga, kei au te hiahia.

You have the goods, I have the need.

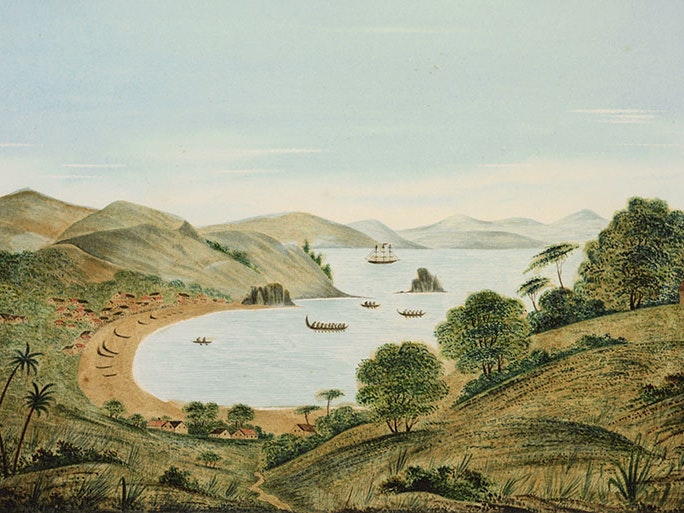

Whalers started hunting the oceans near New Zealand before the 19th century. By 1805, whaling ships called regularly at New Zealand’s Bay of Islands. Māori offered them fresh food and water, and sometimes women. In exchange, Māori received manufactured goods, clothing, and sometimes muskets.

Unknown artist, Whaling off the North Cape, New Zealand. From the book Early History of New Zealand Brett’s Historical Series: From Earliest Times To 1840-1845, by Richard Arundell Augur Sherrin and J. H. Wallace, edited by Thomson W. Lays (or Leys), 1890, book. Gift of Charles Rooking Carter. Te Papa (RB000042)

Some British whalers turned their attention from the open ocean to New Zealand’s coastal waters, where right whales came to give birth.

The whalers set up shore stations all around the country. Here, Māori and British worked alongside each other catching and processing the whales. Both groups felt they benefited. Māori learned new skills and acquired manufactured goods. The British gained access to a land base and a local labour force.

Marriage between whalers and Māori often forged a bond that secured the protection of local rangatira.

Thom’s Whaling Station, Porirua, from Pictorial illustrations of New Zealand, 1848, London, by Samuel Brees, Henry Melville Senior, John Williams and Co. Te Papa (RB001334)

Some Māori took work on ships. They travelled to places as diverse as Australia, Asia, North America, England, and Europe. However, they were sometimes ill-treated on board, abandoned in foreign ports, or cheated of their wages.

As early as 1805, Philip King, British governor of New South Wales, was discussing the problem with Māori in Sydney, but in practice he couldn’t do a thing. Britain had no control over its citizens once they left British-owned territory. And it had no authority either in New Zealand or on the high seas.

New Zealand’s high-quality timber was sought after in Britain and Australia. Māori and Pākehā set up joint ventures to export it. Boat-building started here, too.

James Bragge, Ecatahuna [Eketahuna], The Forty Mile Bush, NZ, from the album Views of New Zealand Scenery/Views of England, N. America, Hawaii and N.Z., about 1875, black and white photograph, albumen silver print. Te Papa (O.011671)

Flax fibre had long been used by Māori for many purposes. But British traders wanted it for one thing – to make rope for ships’ rigging.

In the 1820s Māori sold flax in return for goods such as muskets and blankets. They offered their services to prepare and bring the flax to collection points for Pākehā traders to export.

***

This content was originally written for the Treaty2U website in partnership with National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa and Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o Te Kāwanatanga in 2008, and reviewed in 2020.

One item the Pākehā visitors brought caused more upheaval than any other – the musket. At the start of the 19th century, these guns were the norm on European battlefields.

From 1814, Christian missionaries from Britain began building up friendly relationships with Māori. Mutual trust grew, and eventually this helped the British government gain influence here.

Before 1840, the British government had no legal power to protect its citizens while they were in New Zealand – nor could it make unscrupulous ones obey British laws. This was a problem. Māori, British traders, and missionaries all expressed their dissatisfaction.